OCJP in the News

Gov. Lee Announces Strong Families Grant Program

The Handle With Care program is a statewide initiative of Tennessee and the brainchild of OCJP Deputy Director Daina Moran. It becan with a grant to the Tennessee Association of Chiefs of Police and now it is with Tennessee Bureau of Investigation.

The Tennessee Bureau of Investigation is improving turnaround time to test rape kits, thanks to some help from the OCJP, which secured federal funding to help the bureau process the kits.

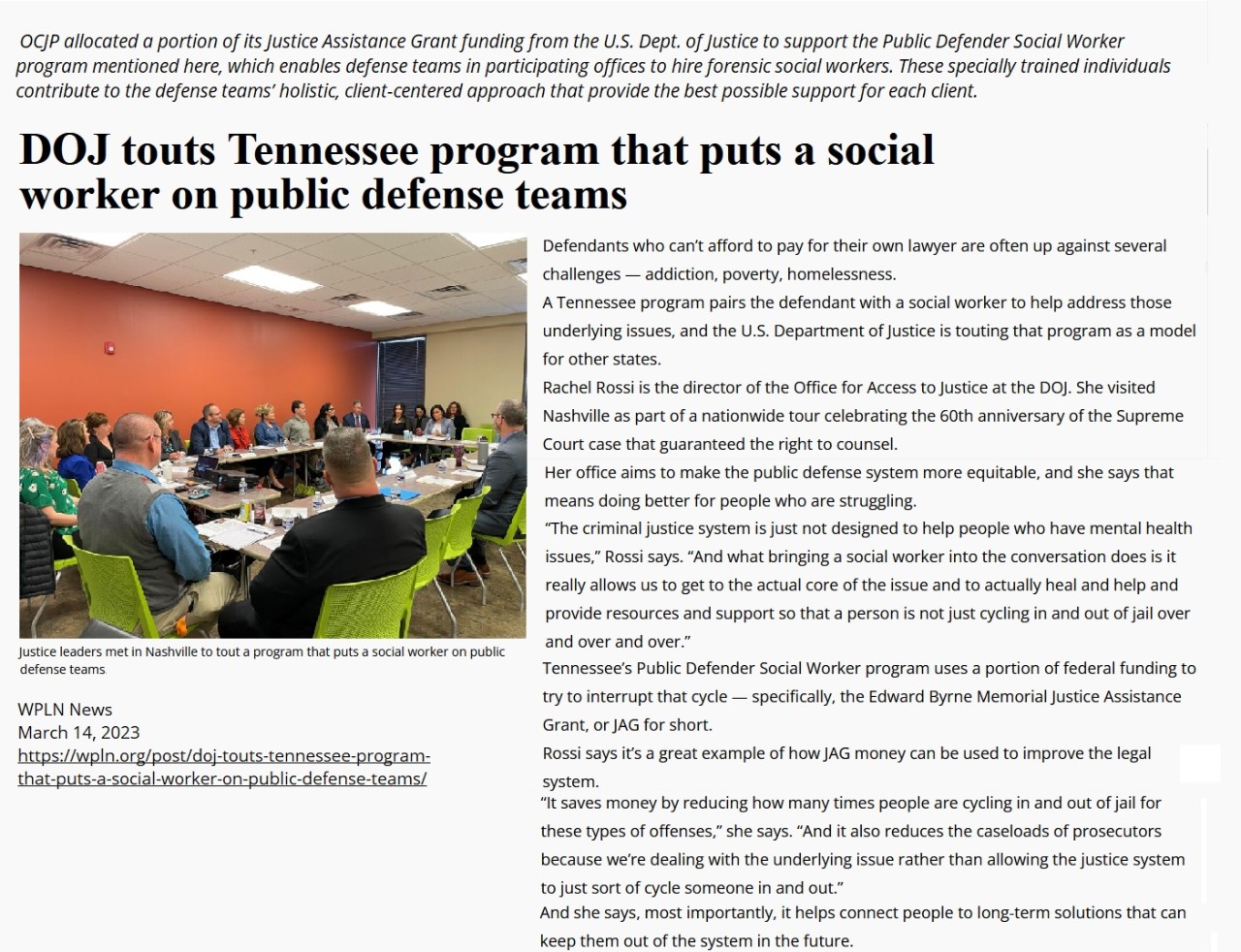

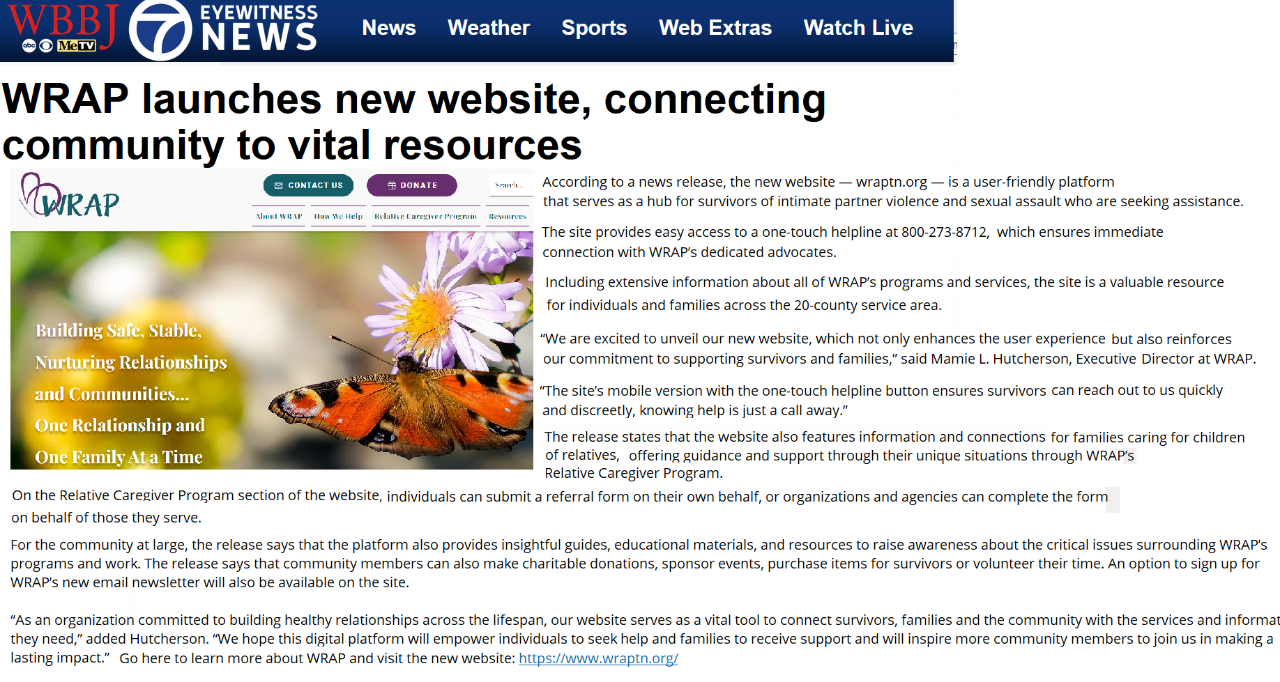

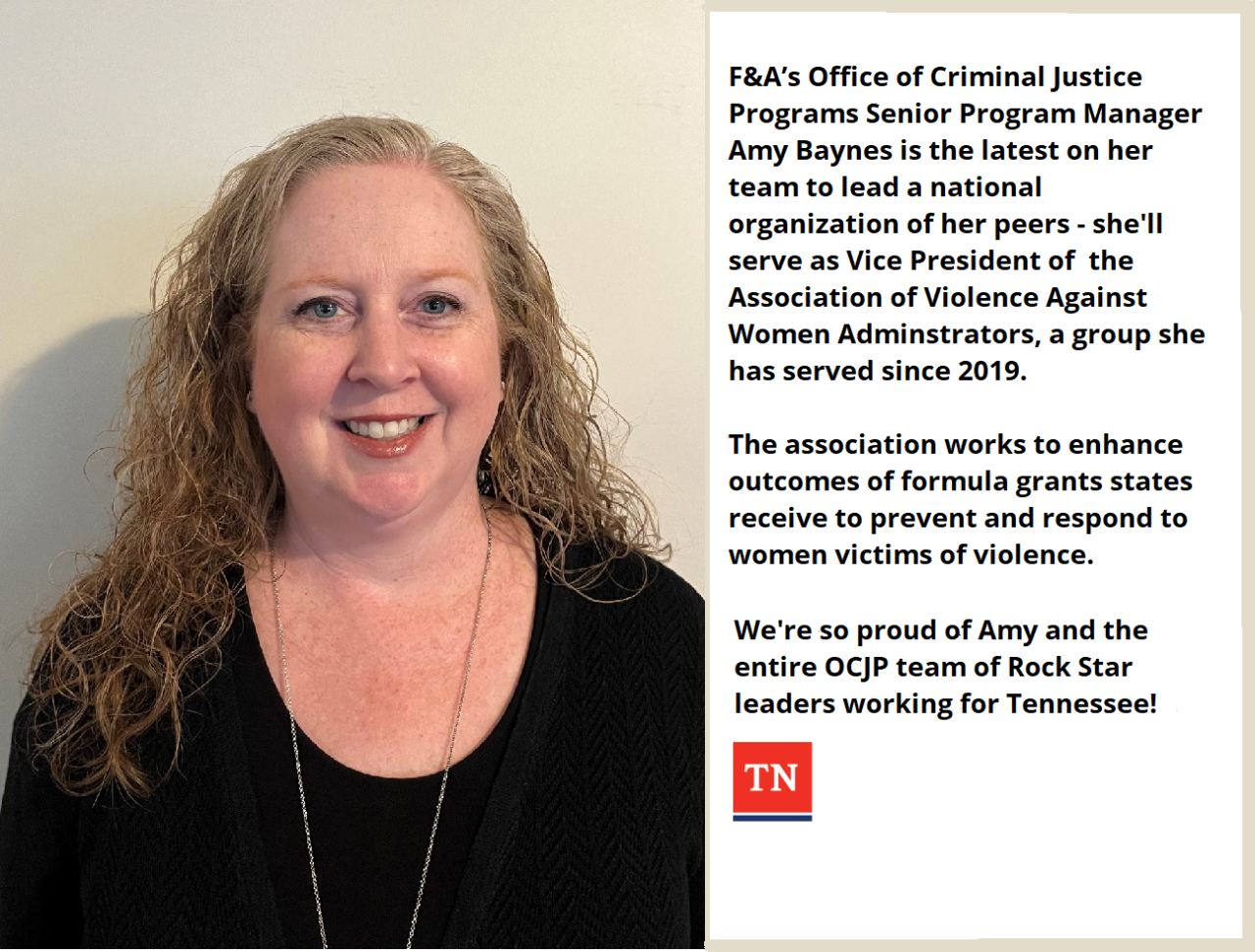

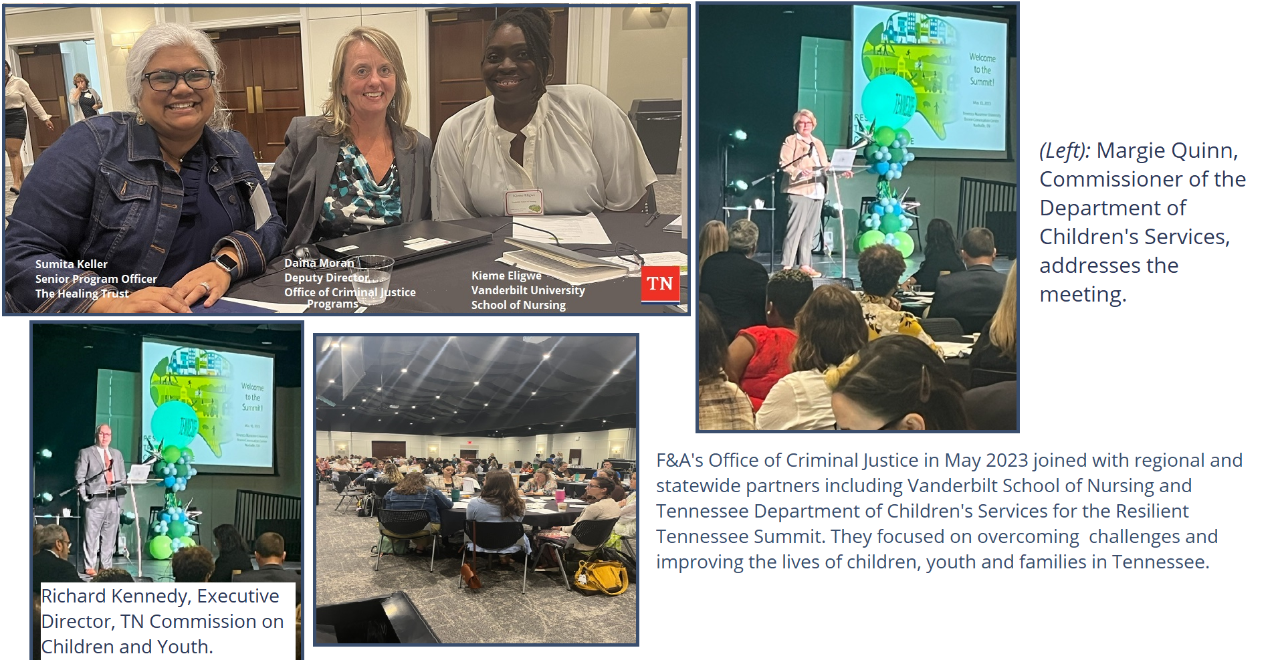

F&A's Office of Criminal Justice Programs works to be a collaborator and partner with our grant recipients.

OCJP brought together the state's 14 Family Justice Centers on June 21 and 22 at Pickwick Landing State Park conference center. About 100 people attended, all involved in services for domestic violence victims. The Family Justice Centers bring together all services a domestic violence victim might need under one roof. Otherwise, the services are scattered across a city or town, making it even more difficult for victims to separate from their abusive situation. The conference drew domestic violence and sexual assault services agencies, district attorney offces, law enforcement agencies, court systems, legal aid agencies and others to celebrate achievements and look toward future growth, attending workshops providing practical knowledge and solutions-based strategies for strengthening collaborative work.

Members of F&A’s Office of Criminal Justice Programs in June led Conferences on Crimes Against Women, thanks to a federal grant secured by OCJP to send prosecutors and victim witness coordinators from across the state. The conference featured more than more than 200 workshops, case studies and hands-on computer labs taught by local and national experts. The goal: a coordinated community response for all crime victims in Tennessee.

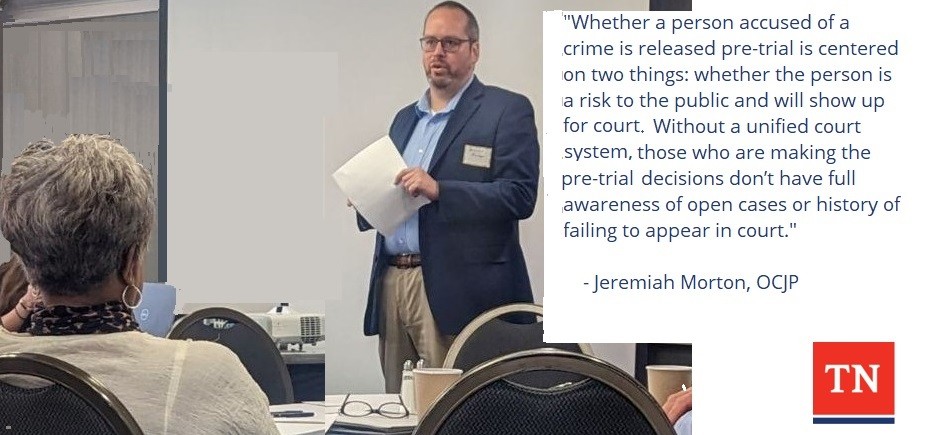

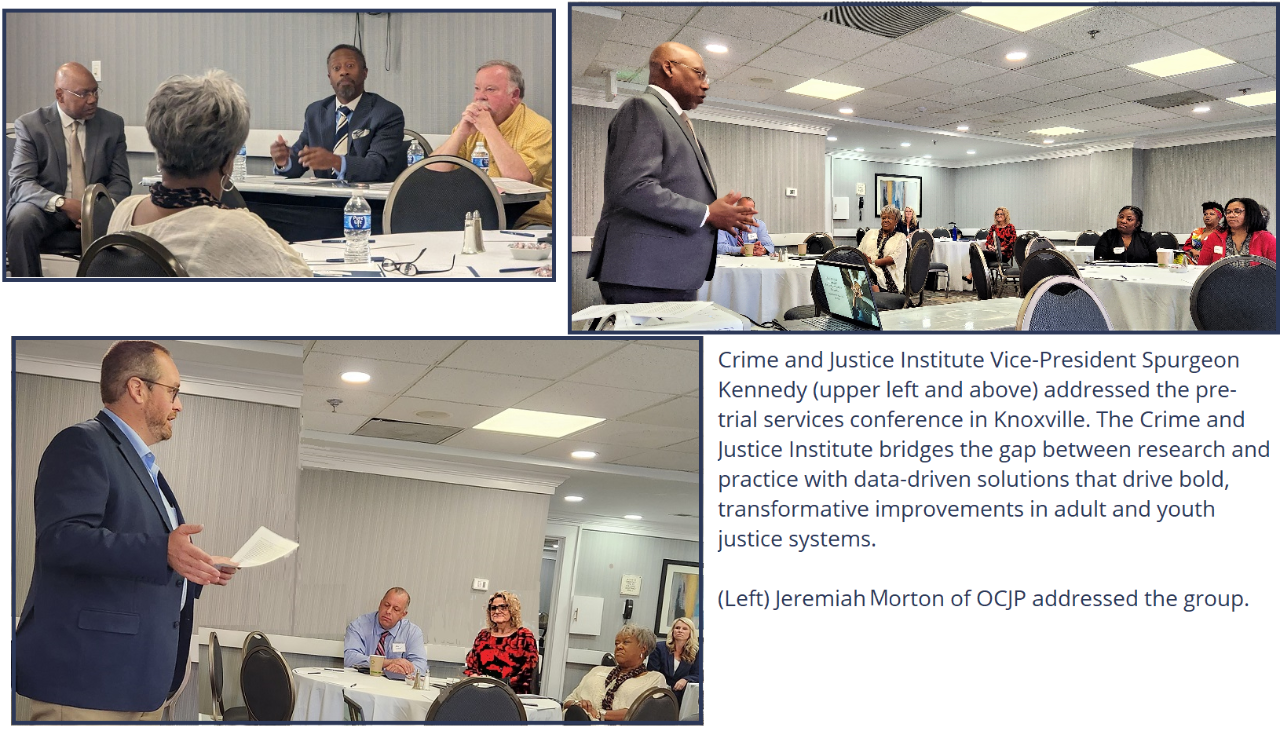

OCJP and the Crime and Justice Institute in May hosted free events throughout Tennessee highlighting best practices and innovations in pretrial services. The events, funded by the Office of Criminal Justice Programs, featured national speakers and local leaders in law enforcement, courts, and pretrial services.

Topics included:

- Risk-based decision models that improve court appearance and public safety

- Innovative programs that Tennessee law enforcement, judges, and pretrial leaders started to solve local challenges

- Practical tips on how to start effective, cost-efficient programs with limited resources

Spotlighting Safe Spaces Throughout Tennessee

OCJP has worked with the Tennessee District Attorneys General to empower victims of crime by providing a safe, comfortable space in the courthouse. These Safe Spaces are essential for victims of crime as they provide a confidential and secure environment to share their experiences and receive support, helping victims to feel safe and comfortable during the court process and ensuring that their privacy and sense of dignity are maintained. OCJP has helped by securing federal funds for Safe Spaces across the state.

Many of the Safe Spaces were also renovated recently as part of the Safe Courts Grants from OCJP. Click here to view more.

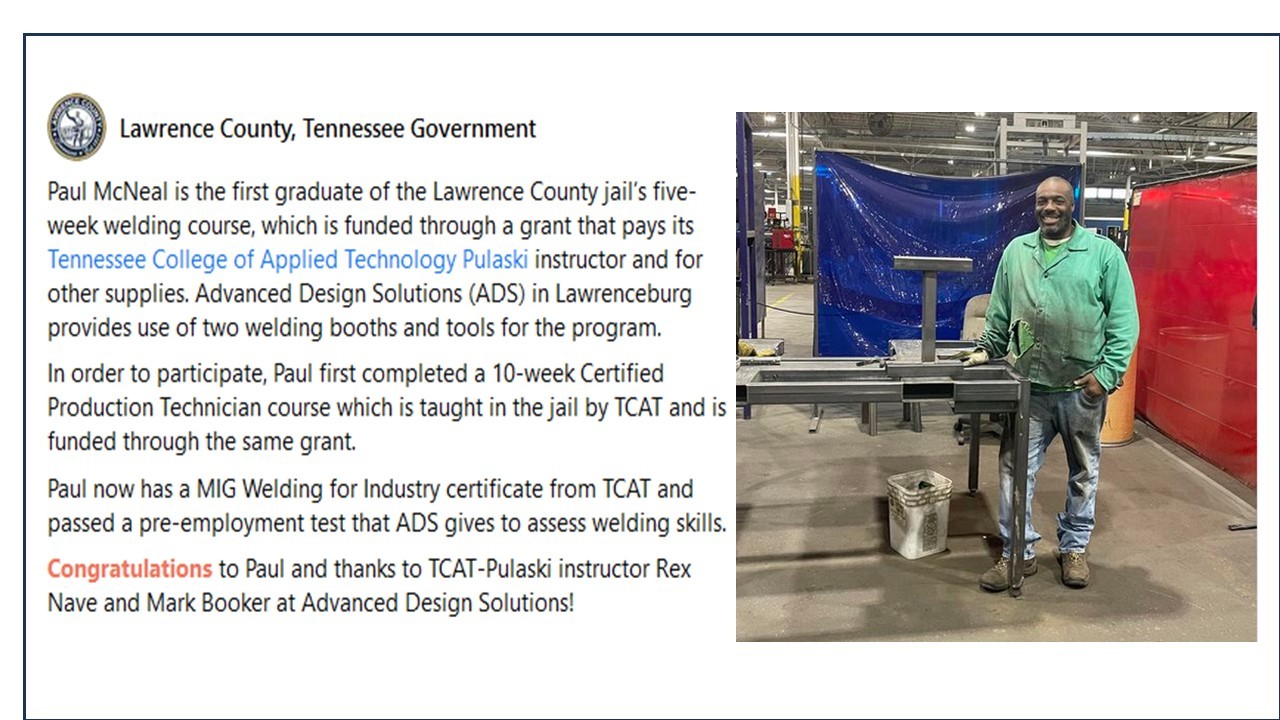

This great outcome is just one of literally hundreds made possible through OCJP grant-writing efforts.

The other first responders: Covenant shooting victim responders describe devastating day

Tennessee was among the first states to adopt an immediate response to survivors mass violence events, first activated minutes after the shooting.

By: Anita Wadhwani - April 18, 2023 9:03 am

Valerie Craig was between appointments, in her car, when she got the call: there had been a shooting reported at The Covenant School minutes before, District Attorney Glen Funk told her. He was on his way. A family assistance center was being set up at Woodmont Baptist Church.

Funk’s call to Craig, cofounder of Tennessee Voices Victims, set in motion a carefully crafted plan to activate the other first responders to the shooting — those focused exclusively on the needs of victims and their families.

Tennessee was among the earliest adopters of so-called Mass Violence Victim Response protocols, created in the wake of previous tragedies like the 2017 Las Vegas concert shooting that killed 58 people, injured 500 and sent thousands more scattering to nearly a dozen makeshift meeting points – a chaotic aftermath that also compounded survivors’ trauma.

The Tennessee Mass Violence Advisory Council was created in 2020 to avoid such scenarios in Tennessee, creating protocols that guided the victim response to The Covenant School shooting last month.

The purpose of having such protocols in place is “to take away the chaos and crisis,” said Jennifer Brinkman, director of the state’s Office of Criminal Justice Programs.

“As horrible as it is, to help victims in crisis you really need to have plans in place,” she said. “We’re one of the few that has that here, not just the law enforcement response. We have a plan in place for victim response.”

On March 27, in the minutes after three children and three adults were killed at The Covenant School, the victim response plan was activated.

At least 40 people from multiple agencies — at the scene and in support roles — arrived equipped with crayons and paper, stuffed animals and fidget toys, gum and water. They canceled all their counseling appointments, marshaled resources and coordinated federal funding for an immediate victim response.

The following account of how the victim response unfolded that day comes from Brinkman, Craig, Kimberly Page and Amity Griffith-Taylor with the city’s Family Intervention Center, and spokespersons for Funk and the Metro Nashville Police Department.

The first calls

Funk was notified immediately about the shooting from a top official with Metro Police after the first 911 calls came in starting at 10:13 a.m.

Funk along with Deputy District Attorney Roger Moore and a top investigator sped to the scene, calling Craig at about the same time the shooter had been taken down. Police said that occurred at 10:27 a.m.

Craig, still in her car, quickly reached Verna Wyatt, Voices for Children cofounder, who — in turn — contacted Brinkman.

Many of the counselors and advocates who needed to respond have jobs that are funded by federal grants that limit their activities. Other federal funds to cover the cost of counselors’ time needed to be immediately tapped, too — behind-the-scenes bureaucratic actions that nevertheless are critical to freeing victim counselors and advocates to respond.

While Brinkman worked with the federal government on funding questions, Craig and Wyatt had more calls to make. Craig’s second call of the day was to the Metro Nashville Police’s Family Services Center.

Staff at the Family Service Center provide free counseling and other services to victims of violence in Nashville. Their days are busy with counseling appointments — last year they provided more than 6,000 individual and group sessions. They also respond to crime scenes to provide an immediate victim crisis response. On any given day, one counselor is always on call to be able to respond to victims’ needs.

The first reports about the Covenant shooting made clear that more personnel would be required than one on-call counselor.

Page and Griffin-Taylor first began tapping counselors who were not already in a counseling sessions to go to the site. Then they pulled counselors conducting group sessions. Soon, however, they realized the whole team would be needed. They canceled all appointments so every available counselor — 10 or 11, they said — could head to the scene. One employee and two interns were left behind to take calls.

As the victim response was being activated, Midtown Hills Precinct Commander Dayton Wheeler was talking with the staff at Woodmont Baptist Church to establish a family resources center — a place for children, teachers and staff away the crime scene. Metro police personnel also contacted Metro Nashville Public Schools to send school buses to transport children, teachers and staff from Covenant to the church.

By 11:17, police had cleared the way for victim responders — from the Family Intervention Center, Voices for Victims and elsewhere — to get to the church’s reception area to coordinate with each other. By 11:30 a.m. the entire victim crisis team was in place.

Inside Woodmont Baptist Church

Victim responders described their work at Woodmont Baptist that day in general terms.

Inside the church, children remained with their teachers on the lower floor of the building. Parents and siblings of Covenant students gathered upstairs in the church’s sanctuary.

Upstairs, the counselors, advocates and volunteers got to work; one created a spreadsheet to track parent information and check ID’s — information that would be used to reunify parents with their children and for follow-up in the days, weeks and months after the shooting.

“You have parents who are super anxious, so helping them stay calm and have the information they need is what you need to do,” Craig said of the initial response. “We are also clarifying where are the parents who might be getting information about the deceased.”

Strictly speaking, no counseling work is provided at the scene, only support — which can take the form of providing water, snacks, serving as a sounding board and validating feelings, said Kimberly Page, division manager for the Family Intervention Program.

“Sometimes people second-guess, say ‘I should have done this or that differently,’” Page said. “We’re letting them know, too, that your brain might not be ready for this and that’s okay.”

Downstairs, “we let the children be children,” Page said. The children remained with their teachers.

Counselors arrived with stuffed animals, squeeze toys, crayons and paper — and snacks. Teachers wanted gum. Craig had some in her car.

Later, the responders also had the task of reuniting children with their parents. The reunifications took place in private rooms, with one counselor escorting a child and another escorting a child’s parents and siblings into a room together.

“We had to think: how do we safely and effectively put these families back together,” Craig said. “From checking IDs to figuring out how to put them back together in a room.”

The entire process took hours. By 3 p.m., more than four hours after the shooting, the last parents and children had been reunited. “The reality is some parents sat there a long time,” she said.

By then the Office of Criminal Justice programs had a prepared a resource guide to distribute to parents, teachers and staff — information they may need to seek mental health services, state victim compensation funding and other resources over time.

Teachers and staff last to leave

“After they all left, it was transition time,” Craig said. Food for teachers and staff was brought in, counselors were made available to them and Metro Police and school teachers and staff held a briefing.

Woodmont Baptist is a little over two miles from The Covenant School. At the end of the day, the victim responders worked to coordinate transportation of The Covenant School staff back to their cars, in the school parking lot.

The victim response has continued since the day of the shooting. Days afterward, responders helped sort belongings retrieved from inside the school — purses, keys, wallets, the contents of lockers — and return them to their owners. The spreadsheet they created with the names of parents and teachers is used to follow up to provide services to those who want them. They have worked with families through the first Easter after the shooting and through six funerals, Craig said.

“This is a marathon,” Craig said. More than two years after a Christmas Day bombing in downtown Nashville forced terrified residents to flee — and some to lose their homes — responders are still meeting to talk over ongoing victim needs, she said.

The victim response to The Covenant School shooting may take even more time, she said.

For the responders, who are all trained in national mass violence response, there is also the need to recover. Staff at the Family Intervention Center have been given a day to work remotely, while counselors have been brought in to help anyone needing one. They’ve also gotten some outside help: a massage therapist who learned about their work in the Covenant Shooting has come in two weeks in a row to provide free 25-minute table massages. A yoga studio has stepped up to offer free classes.

“They take care of the citizens and people of Nashville,” Page said. “They also need to practice self-care.”

Note: The Office of Criminal Justice Systems has worked to secure federal funding to relieve delays in processing rape kits, as referred to in this article.

Class action suit over rape kit delays moves forward in Memphis, but survivors can’t savor relief

As the suit over a backlog of 12,000 rape kits proceeds, two Democratic lawmakers work a bill that require processing of kits within 30 days of submission

Debby Dalhoff says she’s always been a happy, outgoing person around friends and family.

“What they don’t know is when I sit on my back porch at night, what goes through my mind,” said the 68-year-old retired FedEx manager. “It’s constant. It never ends. That inner demon that you can’t get rid of until we can get some closure.”

Dalhoff is one small step closer to closure — maybe — with last month’s ruling by a Shelby County Circuit Court judge that the lawsuit Janet Doe v. City of Memphis, over the decades-long mishandling of thousands of rape investigations, could proceed as a class action. This case began winding its way through the courts in 2014, not long after the Memphis Police Department revealed a backlog of more than 12,000 forensic rape exams, or rape kits.

Dalhoff is one of dozens who signed on to that lawsuit, and has been hoping for years that it would get a class-action certification. She calls the recent ruling a milestone, but only a “breather.”

She says she won’t celebrate yet, with all the work that still lies ahead. Attorneys have to track down as many survivors as they can to join the class action; that is, those who are still alive, because some of the mishandled cases date back nearly half a century.

“I’ve thought about volunteering my time from a clerical standpoint, see if there’s anything I could do to help [ attorneys] build a spreadsheet, and contacting these people,” said Dalhoff, over the phone from her home in Memphis.

She takes a deep breath. “I shouldn’t even have to be doing all this.”

Dalhoff is tired. She’s been seeking closure for 38 years, and for nearly a decade now has been doing the investigative legwork that police never did. When she was 29, Dalhoff and her roommate were blindfolded, gagged, hogtied, raped and tortured for hours, by a man who then washed off traces of himself on them and even vacuumed the house, taking the vacuum cleaner bag with him.

“Think about this, in 1985 DNA wasn’t that popular, but obviously this person was someone who knew something about a cleanup, DNA. Because of that I was told in the beginning of my investigation that they were looking for someone possibly in law enforcement, fireman, paramedic, policeman. So they always had that in the back of their mind.”

Years went by, though, without any new information. When she heard about the massive backlog in 2014, she started calling the police again, obtained her case files and had her case reopened. In 2015, an MPD officer told Dalhoff her evidence was tested, but no DNA was found.

“Well, that’s a bold-faced lie,” said Dalhoff, “because [former Shelby County District Attorney] Amy Weirich told me that my kit had never been found, had never been tested. In fact, I was able to then obtain the documents that showed where every piece of my evidence, not my sexual assault kit, but [other] evidence that could have had DNA on it…was all destroyed.”

Dalhoff’s rape took place before DNA testing became a widespread practice, and before the Memphis Police Department gained access to an FBI database of DNA records called CODIS, where samples can be matched. That explains some of the backlog, until about 20 years ago, but not the disorganized storage of thousands of kits across the city. Or the destruction of countless others, in part because of storage overcrowding, but also in the erroneous belief that the statute of limitations on the cases had passed.

Dalhoff saw documentation that everything from her bed linens to the bindings used in the attack were dumped in a Memphis landfill in the 1990s.

“I had so much high hopes when I found out about the backlog, to then find out [my kit’s] at the bottom of a dump. How much lower can it be?” said Dalhoff. “They let perpetrators run free that could’ve been in jail. They’ve destroyed so many women.”

Thousands of survivors never saw justice, and an untold number of rapists would continue to attack others. Based on the M.O. of Dalhoff’s assault, authorities told her they believed the same man — a former neighbor and firefighter who has since died — was responsible for raping at least four other women. And he grew increasingly vicious, even running a needle and thread through one victim’s nipple, to yank on it.

“One of the most heinous crimes”

What’s striking about a case like Dalhoff’s is that it’s not a he-said/she-said version of events reflective of most sexual assaults, which are committed by someone the victim knows and which police and legislators nationwide have been slow to even recognize as a crime.

Still, Dalhoff’s case languished, uninvestigated, for decades. It’s that kind of negligence that attorney Gary Smith, who is representing the class-action survivors, said helped them establish that while sexual assault is “one of the most heinous crimes that there is, [it] did not have a priority within the sexual crimes unit” of the Memphis Police Department.

Smith calls the recent ruling “a huge victory, but it doesn’t portend a quick end to the case by any means. Unless the city wants to see this thing come to an end.” So far, though, he said there’s been no talk of a settlement from the city.

Memphis Mayor Jim Strickland declined to share his thoughts on the ruling, or the possibility of a settlement before the case goes to trial. A spokeswoman for the mayor told the Tennessee Lookout, “We can’t comment on litigation.”

How a system failure left a rapist free to attack again

Smith also represents Alicia Franklin, whose lawsuit against the city of Memphis was dismissed the same day that the class-action was certified, by a different judge. Franklin, who is Black, was raped at gunpoint, in 2021, by Cleotha Henderson, who in Sept. 2023 would kidnap, rape and kill Eliza Fletcher, a white kindergarten teacher whose case received national attention.

The DNA results from Franklin’s rape kit were reported after Fletcher went missing; indeed, Henderson was charged with Franklin’s rape after he was already in custody over Fletcher’s murder. Both women’s rape kits were submitted by MPD to the Tennessee Bureau of Investigation for processing. According to a TBI statement, Franklin’s was not expedited, nor was there any suspect information attached to it, even though she knew Henderson’s name. The rape happened on what was meant to be a dinner date; the two met through a dating app.

State Sen. London Lamar says Fletcher’s case “put the idea of rape kits back into the public eye and made it a pressing issue,” which is good. However, she added, it’s no secret that some rape kits get preferential treatment within an already flawed system.

“When black girls go missing and get kidnapped and raped, are we stopping the whole police force to go look for them? No,” said Lamar. “Are we the public marching and doing candlelight vigils for them? No. So we also as a society, as a legislative body, have got to realize that there are still lives that are more valuable than others in the way that we handle people’s cases and our criminal justice system.”

The Memphis Democrat has a bill (SB0014/HB0024) working its way through the General Assembly — it passed unanimously in the state Senate, but still has to clear the House — that would require the TBI to process all kits, once they’ve been submitted by law enforcement, within 30 days. According to the TBI, rape kit processing currently varies from 30 to 56 weeks, depending on the city.

If Lamar’s legislation, co-sponsored with Rep. Bob Freeman (D-Nashville) passes, it could help level the playing field, close the racial disparity gap and prioritize rape investigations overall.

Yet Lamar knows that neither race nor the clock are the biggest obstacles in Tennessee.

Processing rape kits takes much less time than know-how and people power. Training scientists to process a sexual assault kit takes at least 18 months, according to the TBI. Keeping them in Tennessee takes more competitive salaries than the state has been offering.

The TBI has not hidden its need for more money, to hire dozens more scientists, but the agency has not received the budget bump it requested from Gov. Bill Lee’s administration. However, since March, the TBI has secured $1,850,000 in grant funding, to outsource 858 kits to out-of-state labs. So far, they’ve sent 550 to Florida, and agency spokesman Josh Devine says they plan to outsource the remaining 308 in early July.

Deborah Clubb, who is part of the Memphis Sexual Assault Kit Task Force created by former Mayor A.C. Wharton, finds the never-ending struggle to process rape kits disheartening.

“I have worked these years with police leadership who really wanted to make amends, so it’s been very hard for me to see the new backlog,” said Clubb, a veteran reporter and longtime advocate for survivors of sexual and domestic violence, who also heads the Memphis Area’s Women’s Council.

“Whether it’s the investigating, or the testing of kids or the prosecuting, these sex crimes are just going to keep on keeping on and they’re going to be older and older,” said Clubb. “And people who are hurt are going to be less and less willing to get into that treadmill system and put themselves through the agony of having to think about it.”

According to the Rape Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN), in the US someone is sexually assaulted every minute, with nearly half a million victims age 12 and up every year.

These crimes often lead to much higher risk of suicide among survivors, and frequent post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Research shows that combat veterans make up less than one percent of all PTSD cases in the US — while sexual assault victims comprise one-third of all diagnoses.

A second assault by the city

Dalhoff knows all too well the psychological and physical toll of sexual assault, though she says what followed was even worse. It’s not uncommon for survivors to call the physical assault less traumatic than others’ reaction to it, or lack thereof, especially from the criminal justice system.

“I never felt sorry for myself or anything like that,” said Dalhoff. “If anything, that initial rape made me a better person. Because it made me appreciate how precious life is. What has eaten me alive is what the city of Memphis has done to me. As I say it, I feel like I’ve been raped twice.”

Once by the perpetrator, she says. And once “viciously, by the city of Memphis.”

These days, she takes long walks in nature, to clear her head of “reality” and recharge for the continued fight. Dalhoff says she wants the class action to be resolved, and a formal recognition by the city of Memphis of all harm that was done, while her 91-year-old mother is still alive.

“She has walked through every step of this with me,” said Dalhoff, the only time she tears up in the hour-long conversation. “I want closure before my mom leaves me. I want justice before my mom leaves me, because she deserves it more than I do.”

Office of Criminal Justice Programs staff went to Chicago in April for the End Violence Against Women International - EVAWI conference on sexual assault, intimate partner violence, human trafficking and elder abuse. They’ focused on promising practices and emerging issues to respond these crimes in all of Tennessee. Rachel Pugh, Amy Baynes, Valerie Steakley and Katie Davis