Insects

Insects are the most diverse group of animals; they include more than a million described species and represent more than half of all known life. Humans regard certain insects as pests, and attempt to control them using insecticides, and a host of other techniques. Some insects damage crops by feeding on sap, leaves, fruits, or wood while some are parasitic and may vector disease. Some insects are considered ecologically beneficial as predators and a few provide direct economic benefit.

The Asian Longhorned Beetle (Anoplophora glabripennis, or ALB) is a threat to America's hardwood trees. With no current cure, early identification and eradication are critical to its control. It currently infests areas in Massachusetts, New York, Ohio and South Carolina.

Hosts include Ash, Birch, Elm, Horse chestnut/buckeye, Golden raintree, London planetree/sycamore, Katsura, Maples, including boxelder, red, silver and sugar maple, Mimosa, Mountain Ash, Poplar and Willow.

Signs and symptoms include Visible Asian longhorned beetles. Adult beetles have bullet-shaped bodies from 3/4 inch to 1-1/2 inches long, shiny black with white spots and long striped antennae, 1-1/2 to 2-1/2 times the size of its body. Chewed round depressions present in the bark of a tree with Pencil-sized, perfectly round tree exit holes. Insects will produce excessive sawdust (frass) buildup near tree bases and unseasonable yellowed or drooping leaves.

Read More: https://www.aphis.usda.gov/plant-pests-diseases/alb

Tennessee’s Boll Weevil Eradication Program (BWEP) is part of a nationwide effort to rid the cotton belt of the most costly insect in the history of American agriculture. The boll weevil first appeared in the United States in 1892, and by 1950 it was estimated to have cost U.S. cotton producers $10 billion.

BWEP has increased cotton yields while reducing cotton insecticide use by 40 - 90%. The Tennessee Department of Agriculture is proud to serve an role in what has been called one of the most successful industry / government partnerships in history.

Program Regions

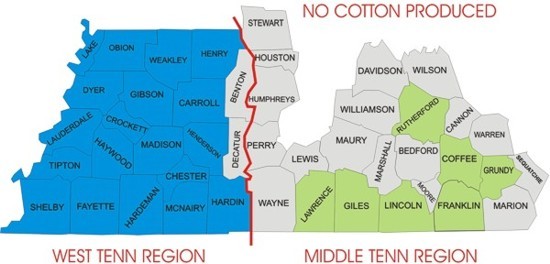

Two distinct boll weevil eradication program regions exist in Tennessee. The West Tennessee Region is colored blue and the Middle Tennessee Region is colored green. These two regions designate where cotton is grown and indicate where the program currently operates. Gray counties and all other counties not shown do not currently produce cotton, therefore the program is not active in those counties.

The Middle Tennessee Region was the first to implement the program in 1994. The region consists of all counties that lie wholly east of the Tennessee River, encompassing what is generally known as Middle and East Tennessee. Currently, only Coffee, Franklin, Giles, Grundy, Lawrence, Lincoln and Rutherford counties produce cotton. This region completed the active phase of the program in 1998 and is now in a post-eradication monitoring phase.

The Middle Tennessee Region is serviced through the Southeastern Boll Weevil Eradication Foundation office in Athens, Alabama. Chris Craft is the Officer-in-Charge and may be reached at 256-729-1402 (office) or 256-366-6324 (cell). Lawrence Flanagan is responsible for all boll weevil traps in Middle Tennessee and may be reached at 256-627-1205. The address of the Athens office is 15900 Shaw Rd., Athens, AL 35611.

The West Tennessee Region implemented the program in 1998 in the southern counties, and the northern counties followed suit in 2000. Three formerly distinct regions have now been combined into one. Benton and Decatur are the only two counties in West Tennessee that do not produce cotton.

The West Tennessee Region is serviced through the Southeastern Boll Weevil Eradication Foundation office in Alamo, Tennessee. Randall Crow is the Officer-in Charge and may be reached at 731-696-3775. The address of the Alamo office is 1398 Old Hwy. 412 N, Alamo, TN 38001.

Links to Related Sites

- USDA Boll Weevil Eradication Program

- US EPA on Malathion

- Tennessee Dept of Health

- National Cotton Council

Other State Programs

Frequently Asked Questions

The Southeastern Boll Weevil Eradication Foundation (SEBWEF) is the organization that was established by growers and state and federal agricultural officials to carry out the eradication program. The foundation is responsible for program operations including mapping, trapping and spraying. SEBWEF sees that the program is implemented consistently from area to area to ensure that boll weevils are not re-infested into areas where the program has been completed. In addition to hiring personnel to conduct spraying, trapping and monitoring activities, SEBWEF also contracts with only licensed commercial pesticide applicators to conducting spraying activities.

The Tennessee Boll Weevil Eradication Foundation, Inc., provides oversight and direction for the program in Tennessee. The TBWEF is responsible for requesting farmer referendums to approve the program in areas targeted for expansion. TBWEF works with the Tennessee Department of Agriculture in collecting farmers assessments and administering the costs of the program. The TBWEF contracts for program services with the Southeastern Boll Weevil Eradication Foundation to carry out eradication activities.

Under state law, the commissioner of agriculture is authorized to conduct a farmer referendum to approve the program in a given area when requested by the Tennessee Boll Weevil Eradication Foundation. For accounting purposes, monies for the boll weevil eradication program are administered through the department’s budget then made available to the Tennessee Boll Weevil Eradication Foundation. TDA provides an additional important function by regulating the use of pesticides. TDA’s Consumer and Industry Services division is responsible for investigating any potential misuse of malathion to ensure public and environmental safety. Regardless of EPA’s low-risk assessment of malathion, TDA is concerned with its proper use, according to label directions. The department has the authority to levy civil penalties or revoke licenses in cases of misapplication depending on the severity of the offense.

The program uses a system of carefully controlled spraying, trapping and monitoring. During the initial phase (year 1) of the program, mandatory applications of malathion are made according to a pre-determined schedule on every acre of cotton at a frequency of every five to seven days starting in August. Then the frequency is reduced to every 10 days during the later part of the growing season until the first frost which usually occurs in early to mid-October. The basis for an automatic schedule is biological in nature and has to do with the need to break the reproductive cycle of the weevil.

During the second phase (years 2 – 5) the automatic spray schedule gives way to an intensive trapping program (one trap per 1-2 acres) where malathion applications are made only in those fields where weevils are detected. This phase of the program will start in May of each year and continue until the first killing frost. As the program progresses, the frequency of spraying is reduced further as the weevil population is eradicated. The final phase of the program involves trapping at a lesser density (one trap per 10 acres) to monitor for boll weevils, with spot sprayings only as required.

Malathion is an insecticide in the organophosphate group of chemicals and is widely used on many different kinds of food crops. Malathion is registered for controlling insects in homes, gardens, institutional settings, agricultural settings and for mosquito control. Malathion saw widespread use in New York City in 1999 to control mosquitoes suspected of transmitting the viral disease encephalitis. It has also been used extensively in California and Florida to control outbreaks of the Mediterranean fruit fly (Medfly). The U. S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) supports a pharmaceutical use of malathion as a treatment for head lice in children. Due to its low toxicity to humans, minimal impact on the environment and high effectiveness on boll weevils, malathion is ideally suited for use in the Boll Weevil Eradication Program. Extensive studies by the U. S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and others conclude that malathion poses little human health or environmental risks.

As a result of the Food Quality Protection Act (FQPA) of August 3, 1996, EPA has been in the process of reassessing risks associated with the use of specific pesticides. One of the first classes to be reassessed was the organophosphates, including malathion. In addition to the revised human health risk assessment for malathion for the purpose of issuing a Reregistration Eligibility Decision (RED) Document, EPA has conducted a special assessment for the use of malathion in the Boll Weevil Eradication Program (which included monitoring in Tennessee) to ensure that the potential exposures to malathion relative to the program are not underestimated. EPA’s Health Effects Division (HED) has concluded that combined dermal and inhalation risks for applicable scenarios do not trigger concern for post-application residential (bystander) exposure in areas nearby fields being treated for boll weevil. Furthermore, these risk assessments are based

on the assumption that malathion will be used at the maximum labeled rate of 16 oz. per acre. All aerial applications of malathion in Tennessee are made at a 10 oz. rate, a 38% reduction from the maximum rate.

98% of the malathion applied by the boll weevil eradication program is applied by fixed-wing aircraft. The remaining 2% is applied by helicopters, high-cycle ground equipment and mist blowers. However starting in 2001 the Southeastern Boll Weevil Eradication Foundation began making greater use of ground equipment and helicopters, especially adjacent to sensitive areas. All aerial applicators utilize Global Positioning System (GPS) technology which not only allows for very precise placement of the product, but provides a record of critical data pertaining to the application process.

The amount of malathion used to kill boll weevils is very small. Only 10 fluid ounces of malathion are used to treat an entire acre (43,560 square feet). That is not enough fill a 12 ounce soda can.

The Tennessee Department of Agriculture regulates all pesticides to ensure their proper use according to label direction. If you suspect that pesticides have been misapplied, you may file a report with TDA’s Consumer and Industry Services division by calling toll-free 1-800-628-2631. An inspector will be assigned to investigate the case. This will require that you provide additional details about the alleged misapplication through follow-up phone calls or visits by the inspector. Samples to detect the presence of pesticides may also be required.

If you have concerns that your health or the health of a family member may have been adversely affected by exposure to pesticides, you should consult your family physician immediately. The Tennessee Department of Health is working with local health departments and the medical community to assess any reported health problems associated with the spraying of malathion. In addition, the Department of Health routinely works with the Department of Agriculture in assessing risk to human health in cases where misapplication is suspected. To date there have been no documented health problems associated with the program.

The most significant benefit is the reduction of pesticides introduced into the environment. After the boll weevil is eradicated from an area, farmers generally reduce cotton insecticide use by 40 to 90 percent. In addition, as cotton becomes more profitable, cotton producers are able to spend greater amounts in the local community for equipment, goods and services. Economic studies have shown that after the program is completed in an area land values tend to increase.

Boll weevils are considered a key pest in cotton production because the insecticides cotton producers use early in the season to control boll weevils also eliminate populations of beneficial insects. With the elimination of the boll weevil comes the elimination of the threat to beneficial insects. With a resurgence of beneficial insects that prey on secondary cotton pests such as bollworms and aphids, the need for pesticide applications to control these secondary insects is further reduced. Growers in eradicated areas can now delay initial spray operations, reduce pesticide rates, use alternative pesticides or lengthen the intervals between sprays to reduce their operating costs while controlling remaining cotton pests.

In 1993, enabling legislation (T.C.A. 43-6-401) was passed relative to the boll weevil eradication program, providing the legal framework for the operation of the program. This legislation does not mandate that a program will be operated, but provides a mechanism by which cotton growers in the state may request, by referendum, the implementation of an eradication program. Upon passage of a grower requested referendum by at least a two-thirds majority, participation in the eradication program is required for all cotton growers in the stipulated area, and the provisions of the statute, and

rule promulgated in accordance to the statute, become effective. This statute also grants authority to the Commissioner to certify a cotton grower's organization and name cotton growers to the organization's board of directors for the purpose of oversight of the program.

The Tennessee Boll Weevil Eradication Foundation, Inc. is the certified cotton grower's organization in Tennessee for the purpose of oversight of the program. Its board of directors and officers are as follows: Allen King, Chairman (Haywood County cotton producer); Gilbert Bradley, Vice-Chairman (Lincoln County cotton producer); Boyd Barker, Secretary/Treasurer (Tennessee Department of Agriculture); Steve Bailey (Crockett County cotton producer); Willie German, Jr. (Fayette County cotton producer); John Lindamood (Lake County cotton producer); R. V. Via (Crockett County cotton

producer)

First of all, the statute gives the Commissioner, or his designated representatives (employees of the Southeastern Boll Weevil Eradication Foundation (SEBWEF) and/or employees of the Tennessee Department of Agriculture) the authority to enter cotton fields for the purpose of carrying out the boll weevil eradication program. Additional requirements relate to the reporting of cotton acreage, the payment of assessments, and the destruction of cotton stalks. These requirements now apply to all regions of the state.

Work units are subdivisions of regions. Each work unit consists of approximately 100,000 to 120,000 acres of cotton. Tennessee has six work units.

Field units are subdivisions of work units. Each field unit consists of approximately 5000–6000 acres of cotton. Each Field Unit Supervisor (FUS) oversees approximately five trappers that service the traps around each field. Each FUS also works with one aerial applicator to schedule insecticide applications as needed. Each aerial application is then followed up by a perimeter application by mist-blower drivers.

By April 1 of each year, report your planting intentions directly to the Field Unit Supervisor(s) responsible for your cotton, making special note of any new cotton fields. You should have the necessary information to contact your Field Unit Supervisor to set up an appointment for him/her to meet you to discuss planting intentions. Otherwise, they may be contacted via the Southeastern Boll Weevil Eradication Foundation work unit offices.

By July 15 of each year, certify your actual cotton acreage at the USDA Farm Service Agency (FSA) office that administers each county where you grow cotton. In the event FSA extends this deadline for their reporting requirements, we will follow suit.

Maximum assessment rates were set by referendum. The maximum rates for 2002 are $35.75 per acre in Region 1, $28.00 per acre in Region 2 and $22.00 per acre in Region 3. In the past rates have been reduced from 20-35 percent by state funding. If additional state funding is received in 2002, the assessment rates will be reduced by that amount. The final assessment rate will be announced as soon as funding measures are finalized.

The deadline for payment of the assessment without penalty is October 15 of each year. Payments after this date will be subject to a $5.00 per acre late payment penalty. All payments should be made at the FSA office that administers each county where you grow cotton. For example, if you grow cotton in Fayette and Hardeman counties, assessment

payments should be made at the FSA offices in Fayette and Hardeman counties for the cotton in each county, realizing there are some administrative exceptions.

Tennessee's 2001 boll weevil eradication program cost approximately $24.4 million. Additionally a loan payment was made to Farm Service Agency (FSA) in the amount of $7.6 million, bringing total program costs to approximately $32 million. Approximately 35% of total program costs were covered by grower assessments, 10% was funded by the State of Tennessee, and 2% by the Southeastern Boll Weevil Eradication Foundation (representing contributions by fellow cotton growers in the Southeast). 13% of program costs for 2002 was funded by the United States Department of Agriculture, representing a major increase in federal funding for2001. The balance of program costs was funded by a loan from the Farm Service Agency in the amount of $14,116,000, representing approximately 40% of program costs. These percentages are subject to change from year to year as assessment rates and costs change.

Since a substantial amount of borrowed funds has been involved for the past four years, the principal loan balance as of December 31, 2001 was $32,306,278. This year-end principal balance should have peaked with repayment in full, including interest, occurring during the seven-year payment phase of the program.

Decades of experience have shown that destruction of cotton stalks is an integral part of successful boll weevil eradication, effectively removing over-wintering habitat for boll weevils. Therefore December 31 of each year has been established as the deadline to have cotton stalks destroyed. Extensions of this deadline will be considered on a case by case basis and a decision based on meteorological and other conditions.

While the goals are similar, there is a substantial difference in controlling boll weevils and eradicating boll weevils, with the management strategies for the two being poles apart. Under an eradication scenario, specialized equipment and formulations are employed on every single acre of cotton, allowing for a more comprehensive and efficient operation which utilizes the economy of scale and logistical capabilities that only a wide-scale program brings. This is truly a cooperative and coordinated effort, and of necessity must remain so.

Many insects depend on host plants for their very survival. In the United States, cotton is the only host plant boll weevils have upon which they depend for reproduction and survival. Therein lies the crux of this unique opportunity to eradicate what has been described as the costliest agricultural pest in U.S. history. We can eradicate boll weevils because we can precisely target where they are – cotton fields. Other, secondary cotton pests have a wide host range and can easily survive on other Tennessee crops and/or plants.

Insecticide applications for boll weevils will kill beneficial insects in cotton fields whether applied by the individual cotton grower in the process of controlling boll weevils, or by the boll weevil eradication program. However, the beauty of this program is that successful boll weevil eradication brings a 40-90% reduction in cotton insecticide use, whereas perpetual insecticide applications at pre-eradication rates are necessary under control scenarios. With the boll weevil, and subsequent insecticide applications, out of the picture, beneficial insects can flourish and perform their vital role as predators of secondary cotton insects.

Normally, the active phase of the program lasts approximately 4-5 years, with the most intense insecticide applications occurring in the first two years. Your cooperation is a key element in speeding up the process. Keep in mind that program personnel must be able to navigate around the perimeter of cotton fields for trap placement and service, and for mist-blower insecticide application as necessary. Every effort to assist us in maintaining our traps and in providing a relatively clear passage around the perimeter of your fields will not only be much appreciated but will speed up the program. Although uncontrollable, another factor has major implications for program tenure – extremely cold winter weather. This occurrence can do more to enhance our efforts than any single effort on our part.

Reducing Exposure to Malathion

Malathion is an organophosphate insecticide used since 1956 by public health officials when necessary to control mosquito populations. Malathion is also the insecticide used by the Southeastern Boll Weevil Eradication Foundation to treat cotton fields for boll weevils. When applied in accordance with the rate of application and safety precautions specified on the label, malathion can be used without posing unreasonable risks to human health or the environment. Because of the very small amount of active ingredient released per acre of ground, EPA's scientists found that for all exposure scenarios considered, exposures to malathion were hundreds or even thousands of times below an amount that might pose a health concern.

The proper application of pesticides should not result in the drifting of chemical off target. However, if you still have concerns, here are some suggestions for reducing exposure before and during spraying in your area.

- If you or any family member has chemical sensitivity, contact the Southeastern Boll Weevil Eradication Foundation office in your work unit to tell them where you live. The Foundation may adjust application techniques to minimize exposure when spraying in your area.

- Remain indoors when spraying is occurring to prevent exposure to the spray.

Additional steps could include:

- Closing windows and turning off window-unit air conditioners when spraying is taking place in the immediate area.

- Keeping children away from truck-mounted pesticide applicators when they are in use.

- Covering garden vegetables, bird baths, lawn furniture, swimming pools, etc.

- Providing shelter for pets; bringing food and water dishes inside or covering them.

Considerations for reducing exposure after spraying:

- Stay indoors for a short period after the spraying.

- Empty and re-fill birdbaths and pet water and food containers. Uncover pools, lawn furniture, and children’s' play equipment, taking care not to become contaminated by the items used as covers.

- Wash any potentially contaminated body surfaces promptly with soap and water.

Who to Contact

For general program information, contact…

Southeastern Boll Weevil Eradication Foundation, Inc.

Randall Crow

1398 Old Hwy 412 N, Alamo, TN 38001

Phone: (731) 696-3775 / Fax: (731) 696-3777 / rs.crow@sebwef.org

For farmer questions about assessments, administration, etc., contact…

Tennessee Boll Weevil Eradication Foundation, Inc.

Boyd Barker, Secretary/Treasurer

P.O. Box 40627, Nashville, TN 37204

Phone: (615) 837-5136 / Fax: (615) 837-5025 / boyd.barker@tn.gov

To file a complaint about improper use of pesticides, contact…

TDA Consumer and Industry Services Division

P.O. Box 40627, Nashville, TN 37204

Phone:(615) 837-5148 or toll-free 1-800-628-2631 / Fax: (615) 837-5012 / Regulatory.Services@tn.gov

For health related questions, contact…

Tennessee Department of Health

Bonnie Bashor

4th Floor, Cordell Hull Bldg

425 5th Ave N., Nashville, TN 37247-5281

Phone: (615) 532-2212 / Fax: (615) 741-3857 / bonnie.bashor@tn.gov

Box tree moth is an invasive pest from Asia that has severely damaged wild and ornamental boxwoods in Europe. It was first discovered in North America in 2018 in Toronto, Canada and could invade the United States. If box tree moths were to become established in Tennessee, they would likely have 2-4 generations per year depending on latitude and especially elevation. Box tree moth caterpillars are green and yellow with white, yellow, and black stripes and black spots and would be the only caterpillars to feed on boxwood. The young caterpillars feed on the underside of the leaves while the older ones eat the entire leaf except for the midrib. Most adult box tree moths are white with a brown border.

Read More:

https://extension.psu.edu/box-tree-moth

Emerald ash borer (EAB), Agrilus planipennis, attacks only ash trees. It was first discovered in the United States in Michigan in 2002 and is believed to have originated on wood packing material from Asia. Since then, the destructive insect has been found in numerous states including Tennessee. Typically, the emerald ash borer beetles can kill an ash tree within three years of the initial infestation.

The larvae (the immature stage) feed on the inner bark of ash trees, disrupting the tree's ability to transport water and nutrients. Adults are dark green, one-half inch in length and one-eighth inch wide, and fly only from April until September, depending on the climate of the area. In Tennessee most EAB adults fly in May and June. Larvae spend the rest of the year beneath the bark of ash trees. When they emerge as adults, they leave D-shaped holes in the bark about one-eighth inch wide.

TDA urges area residents and visitors to help prevent the spread of EAB:

- Don't transport firewood, even within Tennessee. Don't bring firewood along for camping trips. Buy wood from a local source. Don't bring wood home with you.

- Don't buy or move firewood from outside the state. If someone comes to your door selling firewood, ask them about the source, and don't buy wood from outside the state.

- Watch for signs of infestation in your ash trees. If you suspect your ash tree could be infected with EAB, refer to the EAB Symptoms Checklist and online EAB Report Form to alert state plant and forestry officials, or call TDA's Consumer and Industry Services Division at 1-800-628-2631.

Resources

Emerald Ash Borer Checklist

Identify Your Tree

Ash trees are easiest to identify when leaves are on the trees; however, it can be identified by looking at the bark in the wintertime.

- Twigs - stout, gray to green-brown with small, lateral round buds opposite each other; terminal bud is large, brown, with leathery scales flanked by two small lateral buds.

- Leaves - oppositely arranged on twig, pinnately compound (leaf is made up of several leaflets attached to a leaf stem), and has 5 to 9 dark green leaflets (usually 7 or 9).

- Leaflets - either no stalks or very short stalks attached to the leaf stem; smooth or sometimes finely serrated on the upper half.

- Autumn color - green ash - yellow and orange; white ash - red and purple.

- Bark - young bark is usually flaky; forms tall, interlacing ridges and deep furrows with age.

Now Check for Symptoms

Once you have properly identified the trees, check ash trees for the following symptoms:

Emerald Ash Borer FAQ

Amended from the multinational Emerald Ash Borer website - http://www.emeraldashborer.info

The natural range of emerald ash borer (Agrilus planipennis) is eastern Russia, northern China, Japan, and Korea.

EAB was first detected in southeast Michigan in 2002. While it is not exactly certain on its mode of arrival, it most likely came in ash wood used for stabilizing cargo in ships or for packing or crating heavy consumer products. It was first detected in Tennessee in July 2010 at a truck stop in west Knox County off of I-40 near the Loudon County line.

In North America, it has only been found in ash trees. All sizes and even very healthy ash trees can be killed. All of Tennessee's native ash trees (green, white, blue and pumpkin ash), as well as many horticultural cultivars (cultivated varieties of ash or hybrids between species of ash), are susceptible to EAB infestation.

Native to China, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, Japan, Taiwan, and the Russian Far East, the Emerald Ash Borer (EAB) was unknown in North America until its discovery in southeast Michigan in 2002. In the United States, EAB infestations have been detected in 35 states and the District of Columbia; Alabama, Arkansas, Colorado, Connecticut, Delaware, Georgia, Illinois, Indiana, Iowa, Kansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Michigan, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New York, North Carolina, Ohio, Oklahoma, Pennsylvania, Rhode Island, South Carolina, South Dakota, Tennessee, Texas, Vermont, Virginia, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. EAB has been found in 5 Canadian provinces: Manitoba, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, Ontario, and Quebec. EAB has also been found in Russia (including Moscow) and Ukraine.

The canopy of infested trees begins to thin above infested portions of the trunk and major branches because the borer (EAB larva) destroys the water and nutrient conducting tissues under the bark. Heavily infested trees exhibit canopy die-back usually starting at the top of the tree. One-third to one-half of the branches may die in one year. Most of the canopy will be dead within 2 years of when symptoms are first observed. Sometimes ash trees push out sprouts from the trunk after the upper portions of the tree dies.

The adult beetle is dark metallic green in color, 1/2 inch-long and 1/8 inch wide. There are several pictures of EAB in the Photo Album and EAB Life Cycle pages.

Although the beetle can have a one or a two-year life cycle, EAB generally has a one-year life cycle in Tennessee. Adults begin emerging in the spring depending on the latitude, elevation, and how warm the winter and early spring temperatures has been. Cooler temperatures over this period (a late spring) delays the adult emergence. The peak of adult emergence in Tennessee is typically in May or early June. It is somewhat later in the higher elevations where Ash is still present. EAB adults live only a few weeks. Females usually begin laying eggs about 2 weeks after emergence. They will lay an average of 40 -70 eggs, which are laid individually within bark cracks and crevices. Eggs hatch in 1-2 weeks, and the tiny larvae bore through the bark and into the cambium – the area between the bark and wood where nutrient levels are high. The larvae feed under the bark until fall (usually October). EAB larvae pass through four instars, eventually reaching a length of 1 to 1.25 inches. EAB larvae overwinter as prepupal fourth instars in a small chamber in the outer bark or in the outer inch of wood. Pupation, which takes 4 weeks, occurs in spring followed by the emergence of the new generation of adults.

Adult EAB can fly at least 0.5 mile from the tree, but generally do not fly far from where they emerge. Many infestations, however, were started when people moved infested ash nursery trees, logs, or firewood into non-infested areas.

Although EAB was first found in southeastern Michigan near Detroit in the summer of 2002, it had probably been present for 10-12 years or more prior to its discovery. It is believed that the population began as a very small number of beetles on solid wood packing material carried in cargo ships or airplanes originating in its native Asia. By 2002, many Ash trees in southeastern Michigan were dead or dying. This had been the case for a few years and was getting worse. However, it was not known until then what was causing this problem.

Healthy ash trees are also susceptible, although beetles may prefer to lay eggs or feed on stressed trees. When EAB populations are high, small trees may die within 1-2 years of becoming infested and large trees can be killed in 3-4 years.

Although biological control efforts against EAB were initiated by USDA, APHIS (United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service) shortly after its discovery in 2002, this has been a process that has taken many years to reach its current state of more advanced development. The focus for many years, especially the early ones, was also on quarantine regulations, infested tree removal, trap development, and survey. APHIS has concluded that the domestic quarantine has not proven effective in stopping its spread. APHIS removed the federal domestic emerald ash borer quarantine on January 14, 2021. APHIS will direct available resources toward non-regulatory options for management and containment of the pest, such as rearing and releasing biological control agents. Tennessee, for the time being, is maintaining the state quarantine against EAB. If this changes, it will be posted on the Tennessee Department of Agriculture – Plant Certification website. To check on the EAB Quarantine status of other states, visit https://www.nationalplantboard.org/members.html. The USDA, APHIS, PPQ (Plant Protection and Quarantine) EAB website is available at https://www.aphis.usda.gov/aphis/ourfocus/planthealth/plant-pest-and-disease-programs/pests-and-diseases/emerald-ash-borer. The Emerald Ash Borer Information Network, a national EAB website that includes links to a treatment publication, maps, history, and recorded webinars, is available at http://www.emeraldashborer.info/.

- EAB is becoming an international problem, with infestations in Canada and the United States. The scope of this problem could reach the billions of dollars nationwide if not dealt with. State and federal agencies have made this problem a priority. Homeowners can also help by carefully monitoring their ash trees for signs and symptoms of EAB throughout the year.

- In Tennessee, an estimated 261 million ash trees on timberland could potentially become infested with EAB. This represents a potential value loss of over $9 billion (USDA Forest Service).

- Timber uses: major export commodity used in furniture, cabinets, flooring, caskets, tool handles, sports equipment (e.g. baseball bats, hockey sticks, canoe paddles), mineland reclamation.

- 127 mills throughout the state report using and processing ash logs (TDF).

- Another 10 million ash trees in urban areas are potentially at risk with a value loss of another $2 billion. (TN Forest Resource Assessment and Strategy (in review)).

- Uses: street/shade/beautification tree widely planted in urban areas due to its fast growth, beautiful fall color, ease of maintenance, and hardiness to urban environment.

- Wildlife uses: seeds of ash are eaten by several species of birds. The bark is occasionally food for rabbits, beaver and porcupine. Cavity excavating and nesting birds often use ash.

If you are in an area that still has apparently healthy ash trees, individual trees can often be successfully treated with pesticides against EAB. If trees are treated prior to attack by EAB, the likelihood of success is much greater. Products designed for homeowners have some restrictions that do not apply to professional products. Treatment programs must also comply with the limits specified on the label regarding the maximum amount of an insecticide that can be applied per acre during a given year. This restricts the number of trees that can be treated in an area per year, especially when relatively high application rates are used or when large trees need treatment. Treatment is not recommended if ash trees are in visible decline. A treatment publication that is a valuable resource for both homeowners and pest control professionals titled Insecticide Options for Protecting Ash Trees April 2019 – Third Edition is available at http://www.emeraldashborer.info/.

If your management goal is to harvest them prior to being killed by EAB, it is important to both scout for early signs of EAB damage (thinning of leaves and die-back at the top of the tree) and to check the map of EAB infested counties. You may also wish to consult with a forester.

Native natural enemies of EAB in Tennessee include woodpeckers and three species of parasitoids (tiny stingless wasps). Four species of parasitoids from EAB’s native range have been approved for release in the United States. Three of these four species are considered established and spreading in parts of the northern U.S. due to favorable climates for them in the colder part of the country. Although one of these four species have been recovered in Tennessee, it may not be established or become sufficiently established to impact EAB populations. More info can be found here https://www.emeraldashborer.info/. The goal of APHIS’ EAB program is to help maintain ash trees as part of the North American landscape. Due to the long life cycle of trees and the large number of ash trees and species throughout North America, it will be many years before we know if biocontrol can protect ash species against EAB. At this time, it appears the northern states will have a better outcome than the southern states due to the excellent suitability of three of these introduced parasitoids to the colder climate of the northern states.

In general, having a diversity of tree species in your yard, on your street or in your community is your best defense against all tree health problems. Plant no more than 10 percent of any one tree species in your yard. Because of the severe nature of the EAB threat, the wisest choice at this time is not to plant any ash trees.

Please refer to the quarantine map in the Plant Certification Section EAB website. If EAB becomes deregulated at the state level, it will be posted in the TDA Plant Certification website. Currently, EAB is regulated in 65 counties in Middle and East Tennessee by the State EAB Quarantine (EAB has been confirmed in all 65 of these counties). The Federal EAB Quarantine was discontinued in January of 2021.

Educate yourself on how to recognize signs and symptoms of EAB and share this information with your neighbors. An excellent website for EAB information is http://www.emeraldashborer.info/.

You can visit http://www.emeraldashborer.info/ for more information on EAB. To report an infested tree in the quarantined/known infested area, please contact your Extension Service County Office or your Area Forester with the Tennessee Division of Forestry. To report an infested tree outside the quarantined/known infested area, please contact either the State Entomologist with the TDA Plant Certification Section at 615-837-5139 (e-mail – Steve.Powell@tn.gov), Forest Health Forester – TDA Division of Forestry at 615-837-5439 (e-mail – Cameron.Stauder@tn.gov), or your Tennessee Division of Forestry District Office.

Hemlock Woolly Adelgid (HWA), Adelgis tsugae, a destructive aphid-like insect pest of eastern and Carolina hemlock, is originally from Asia.

HWA feeds on trees of all ages. The insects attach themselves to the base of the hemlock needles and feed from the new twig growth with piercing-sucking mouthparts. The most noticeable aspect of infested hemlocks is the white masses at the base of needles on the twigs. The adults are small (1/32 inch), oval and reddish purple, although covered with white, waxy tufts.

Limb dieback may occur within two years of the initial infestation on seedlings and saplings. Heavily infested larger trees usually die within four years, although it may take longer than 10 years depending on proximity to other infested trees, tree size, the level of environmental stress and the quality of the growing site.

HWA is established in East Tennessee. In April 2017, HWA was found in Overton County. In March 2017, HWA was found in Warren County. There are now 43 counties in Tennessee that have infestations. The six US states with HWA quarantines are Maine, Michigan, New Hampshire, Ohio, Vermont and Wisconsin. Canada also has a HWA quarantine in effect.

The entry requirements for Hemlocks from infested or adjacent areas vary from state to state. A State Phytosanitary Certificate is required. State summaries may be found at the National Plant Board (NPB) laws and summaries site https://www.nationalplantboard.org/state-law--regulation-summaries.html. For example, Michigan's quarantine does not allow movement of hemlock from an infested or adjacent county into the state. For more information, contact the State Plant Regulatory Official in the state you're intending to move hemlock (contact information at NPB site) or contact the Tennessee Department of Agriculture (Anni Self or Steve Powell) at 615-837-5137.

Resources

Imported Fire Ants (IFA) were accidentally introduced into the United States from South America, beginning in about 1918. The first confirmed sighting of IFA in Tennessee was an isolated infestation in Shelby County in 1948, which was quickly eradicated. Natural migration of IFA was first documented in Tennessee in Hardin County in 1987. Now, much of Tennessee is infested with IFA. Tennessee Imported Fire Ant Areas by County.

Imported Fire Ants look very much like ordinary ants. They are between a tenth and a fourth of an inch in size and reddish brown to black in color. Imported Fire Ants are very aggressive when disturbed and cause a painful sting that produces a small white pustule about 8-24 hours following the sting.

Fire ant colonies build mounds that may be 10 inches or more in height, 15 inches or more in diameter, and 3 feet or more in depth.

A fire ant mound contains a queen (In some areas outside of Tennessee, there may be many queens in a colony), workers, and immatures (egg, larva, pupa). When the colony population is sufficiently large, winged males and females are produced. At a time of favorable weather conditions, a mating flight occurs, after which the queens that survive begin new colonies. A new colony is generally less than a mile away from the colony of origin, but is occasionally 10 miles or more away. In heavily infested areas single queen colonies can reach densities of 20-50 mounds per acre.

Contact your County Extension Agent or the Tennessee Department of Agriculture, Division of Consumer and Industry Services, Plant Certification Section for assistance in identifying potential Imported Fire Ants.

Imported Fire Ants cause harm and economic losses in a variety of ways. Stings from fire ants inflict intense pain to millions of Americans each year with thousands requiring medical treatment. A small number of people develop a life-threatening allergic reaction to IFA stings. The number of human fatalities resulting from IFA stings is not known due to lack of documentation. However, there have been confirmed deaths due to IFA in Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, and Florida. Imported Fire Ants also attack and kill domestic animals and wildlife as well as destroy seedling corn, soybeans, and other crops. Fire ant mounds can damage farm equipment and lawn mowers. IFA are attracted to electrical equipment and chew on insulation, resulting in short circuits and interference with switching mechanisms. Fire ants can shut down air conditioners, traffic signal boxes, and even airport runway lights. Approximately $2 billion in damage, including costs for insecticide for fire ant suppression and eradication, is caused by IFA in the United States each year.

Imported Fire Ant Quarantine

Imported Fire Ants spread into new areas through natural mating flights and through artificial (man-aided) movement of infested products such as sod, baled hay, soil (alone and with other material), plants (excluding house plants) and used earth moving equipment. The rate of spread through natural mating flights is relatively slow in comparison to movement through man-aided means. In 1958, the United States Department of Agriculture, Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (USDA, APHIS), enacted a Federal Imported Fire Ant Quarantine (7CFR301.81) to slow the artificial spread of Imported Fire Ants from fire ant infested (quarantined) areas to non-infested (non-quarantined) areas. The Imported Fire Ant Quarantine includes all of Alabama, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Puerto Rico, and South Carolina and parts of and parts of Arkansas, California, New Mexico, North Carolina, Oklahoma, Tennessee and Texas. USDA IFA Interactive Map.

Within Tennessee, all or parts of 87 counties are quarantined for Imported Fire Ants. The Tennessee Imported Fire Ant Quarantine Rule was established in 1990. Surveys are conducted annually to determine the extent of natural northward migration and to increase the quarantined areas when necessary. Tennessee Imported Fire Ant Areas by County.

Materials Regulated by the IFA Quarantine

The following regulated articles require a certificate or permit before they can be shipped outside the quarantined area:

- Imported Fire Ant queens and reproducing colonies of Imported Fire Ants.

- Soil, separately or with other things, except soil samples shipped to approved laboratories (consult with a State or Federal inspector for a list of approved laboratories). Potting soil is exempt if commercially prepared, packaged, and shipped in original container.

- Plants with roots and soil attached, except house plants maintained indoors and not for sale.

- Grass sod.

- Baled hay and straw that has been stored in contact with soil.

- Used soil-moving equipment.

- Any other products, articles, or means of conveyance of any character whatsoever not covered by the above, when it is determined by an inspector that they present hazard of spread of the Imported Fire Ant and the person in possession thereof has been so notified.

Requirements for Growers Concerning the IFA Quarantine

Under a compliance agreement, a nurseryman in a quarantined area is required to treat regulated articles with USDA/APHIS approved fire ant control products and procedures prior to shipment to non-quarantined counties. Compliance agreements are available by contacting Anni Self, Plant Certification Section Administrator, at the Nashville office by e-mail at Anni.Self@tn.gov, by phone at (615)-837-5313, or by fax at (615)-837-5246.

There has been a change in the treatment frequency and technique involving drenching of Balled and Burlapped (B & B) Plants. This information is available in the Related Link – USDA APHIS PPQ Treatment Manual Section on Imported Fire Ant (February 2015). While chlorpyrifos remains the only chemical option and the total volume of the treating solution must be 20 percent (1/5) the volume of the root ball, plants may now be treated only a total of two times in one day with one half the total drench solution for each of the two treatments. After applying one half the total drench solution for the first treatment, there is a required wait of at least 30 minutes and a rotation of the root ball prior to the application of the second treatment. Rotating or flipping the root ball between applications is required to insure all sides of the root ball are sufficiently treated. The USDA APHIS PPQ Treatment Manual may be accessed on the web at https://www.aphis.usda.gov/plant-pests-diseases/manuals.

Transportation of Regulated Items From Quarantined to Non-Quarantined Areas

To prevent the spread of Imported Fire Ants regulated items may not be moved from quarantined areas to non-quarantined areas unless accompanied by a document that certifies certain procedures have been met to ensure that these items are apparently free from Imported Fire Ants. A state certificate and/or USDA shield must accompany each shipment. This would not apply to a homeowner purchasing a plant from their local store. However, the local vendor in a non-quarantined area should have a certificate stating that the plants have been treated or are apparently fire ant free if they were purchased from a nursery in a quarantined area. Procedures for the movement of other items such as baled hay differ somewhat.

Consequences of Breaking the Imported Fire Ant Quarantine

Since the Imported Fire Ant quarantine is a federal law, violations of the quarantine are considered federal offenses, and these cases would be subject to federal prosecution. In addition to this, the Tennessee Department of Agriculture, Division of Consumer and Industry Services, Plant Certification Section has civil penalty authority in Imported Fire Ant quarantine violation cases.

What Can I Do If I Buy Products Infested With Imported Fire Ants?

Contact an office of the Plant Certification Section or your County Extension Agent to confirm Imported Fire Ant presence so that appropriate steps can be taken to close this potential route of infestation. Consumer education is becoming increasingly important. Retail outlets and consumers are potential routes of spread of fire ants. Regulated items can legally be moved within quarantined counties without being treated, but then be purchased by consumers in adjacent non-quarantined counties who inadvertently spread fire ants into their county. The University of Tennessee Agricultural Extension Service has educational materials available to consumers to assist them in identifying fire ants and minimizing their impact. They can be obtained at your local county extension office.

Related Links

- The Imported Fire Ant and Its Control

- Imported Fire Ants in Tennessee

- USDA APHIS PPQ Treatment Manual Section on Imported Fire Ant (February 2015)

- TX Imported Fire Ant Research & Management

- 2024 TN IFA Quarantine Areas

- Imported Fire Ant Rule

- Labels Available for IFA Quarantine

- USDA APHIS IFA Website

- Quarantine Treatments for Nursery Stock, Grass Sod, and Related Materials - 2015 [PDF 2.28m]

- Mississippi State University – Extension Fire Ant

The Japanese Beetle is a serious pest of nursery, turf, and horticultural crops throughout the eastern United States (except Florida). An article in the 2002 Annual Review of Entomology estimated the annual cost of management for Japanese Beetle in the turf and ornamental industry at approximately $450 million. A native to Japan, it is also found in China, Russia, Portugal, Canada, and the United States. First discovered in the United States by Plant Inspectors in New Jersey in 1916, the Japanese Beetle began to quickly spread (even though control and quarantine efforts were made). After Federal quarantines of nursery stock were discontinued in 1978, the U.S. Domestic Japanese Beetle Harmonization Plan was developed by the National Plant Board to standardize Japanese Beetle quarantine treatments among States, because the elimination of the Federal Japanese Beetle quarantine resulted in considerable confusion regarding interstate shipments. Nurseries must abide by the restrictions of root ball size, soil type, approved chemicals, and timing of treatments in the Harmonization Plan to ship to certain states. The most recent revision to the U.S. Domestic Japanese Beetle Harmonization Plan was completed on June 20, 2016 and is available at www.nationalplantboard.org.

Japanese Beetle adults feed on the leaves, flowers, or fruit of more than 300 species of plants. They are approximately one-third to one-half inch long and have a metallic green head and thorax with copper-brown wing covers. The sides of the abdomen have five white patches of hairs, and the tip of the abdomen has two patches of white hair. Japanese Beetle grubs are pests of turfgrass. They chew grass roots, causing the turf to brown and die. They spend the winter underground in the soil of lawns, pastures, and other grassy areas. In spring, grubs move up near the soil surface to finish feeding, pupate, and then emerge from the ground as adults in late May or during the month of June (cooler climates are later) in Tennessee. Extension Service publications provide treatment recommendations for the public. A good source of general information about Japanese Beetles with bibliographical references is available at https://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/orn/beetles/japanese_beetle.htm.

Light Brown Apple Moth (LBAM) is an invasive pest native to Australia and is now widely distributed in New Zealand, the United Kingdom, Ireland, and New Caledonia. First collected in Hawaii in 1896, LBAM is common in Hawaii as well. LBAM was detected in California (Alameda County) in March of 2007 and has subsequently spread to 22 counties in California. It is a pest that is regulated by USDA and CDFA (United States Department of Agriculture and California Department of Food and Agriculture). LBAM is of regulatory importance because it has many diverse host plants (well over 1,000 species in 120 + genera in 50 + families), including those in nurseries, greenhouses, gardens, and orchards. LBAM larvae will damage leaves and fruit. There is particular concern regarding apple, grape, pear, peach, and cherry. LBAM is a leaf roller moth (Family Tortricidae) of which there are many species. Adults are small with a wingspan of an inch or less. The coloration is variable with an overall yellow-brown color. LBAM is very similar in appearance to native moths in all life stages and can only be identified by an entomological specialist. California is the only state in the lower 48 with an established population of LBAM. Other states, including Tennessee, have placed pheromone traps for LBAM. Tennessee has never detected any LBAM in trapping or visual inspection/survey activities. The only other state to capture any LBAM in trapping is Oregon (only 2 individual catches). The USDA, APHIS (Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service) website on LBAM is available at https://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/terrestrial/invertebrates/light-brown-apple-moth. The CDFA website on LBAM is available at https://www.cdfa.ca.gov/plant/lbam/. The USDA National Invasive Species Information Center on LBAM is available at https://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/terrestrial/invertebrates/light-brown-apple-moth.

The spongy moth has been an important pest of hardwoods in the northeastern U.S. since the late 1800’s (first introduced in Massachusetts in 1869). Established populations exist in all or parts of 20 states and the District of Columbia from Maine down to SW Virginia and west into the upper Midwest to Wisconsin and NE Minnesota. Oaks are the preferred host species for feeding caterpillars, but apple, sweetgum, basswood, gray and white birch, poplar, willow, and many others serve as hosts. Artificial (man-assisted) movement rapidly accelerates the spread of the insect (particularly egg masses) hitchhiking on items that are moved long distances such as nursery stock, vehicles, forest products, and outdoor household articles such as deck furniture. Federal and state regulations require that items to be moved from infested areas to non-infested areas must be carefully inspected and certified to be free of spongy moth life stages. Early detection of artificial infestations/introductions of spongy moth are made possible by the placement of thousands of pheromone traps (to capture adult males) throughout the state each year. As necessary, eradication treatments (including aerial applications) are made to prevent spongy moth from becoming established in new areas away from the established populations. The NE corner of Tennessee is in a transition zone called Slow the Spread (STS) where the management goal is to suppress (not eradicate) spongy moth populations as the front is very close to that area. More information from the USDA Forest Service on Spongy Moth is available at https://www.invasivespeciesinfo.gov/terrestrial/invertebrates/spongy-moth.

Spotted Lanternfly (SLF) was first found in the United States in Pennsylvania in 2014. It is a planthopper native to China and southeastern Asia. In addition to the United States, SLF is present in China, Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Vietnam. Within the United States, SLF has been found in Connecticut, Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania, Virginia, and West Virginia. This invasive insect feeds primarily on Tree of Heaven (Ailanthus altissima), but has many other host plants, including grape, hop, apple, stone fruit, maple, poplar, walnut, and willow. There are many hosts as the immature stages (nymphs) develop, but as adults, they prefer to feed on and lay eggs on Tree of Heaven. Adults and nymphs will feed on phloem tissues of young stems and bark tissues with their piercing and sucking mouthparts and excrete large amounts of honeydew, leading to the accumulation of sooty mold. SLF may lay egg masses on materials/items that can be moved by people long distances as is the case with Gypsy Moth. If this pest spreads, the grape, orchard, and logging industries will be impacted. SLF goes through four nymphal instars before becoming adults. The first three nymphal instars are black with white spots, while the fourth one has red with the white spots. The adults will feed for several weeks and in late summer/early fall lay groups of eggs in rows (egg masses containing 30-50 eggs) covered by waxy deposits on trees and objects in the area. SLF overwinters as eggs and hatch in the spring. The adults are about one inch long and a half inch wide with a striking and unusual color arrangement, especially when their wings are spread. Their forewings are light brown with black spots at the front and a speckled band at the rear. Their hind wings are scarlet with black spots at the front and white and black bars at the rear. Their abdomen is yellow with black bars. They will often feed in large groups, especially as adults and 4th instar nymphs. They are easier to see at night or dusk as they will be found throughout the host plant while during the day, they are more commonly near the base of the plant.

While eradication and state quarantine efforts are underway in the infested areas of the United States, the goal of eradication may not succeed as these efforts were delayed in their start. Eradication efforts largely consist of host (Tree of Heaven) removal and chemical control using trap trees to kill large numbers of SLF. There are links to more information about Spotted Lanternfly at the following web locations: (USDA) https://www.aphis.usda.gov/plant-pests-diseases/slf. (Virginia Extension – Virginia Tech) https://ext.vt.edu/agriculture/commercial-horticulture/spotted-lanternfly.html. (New Jersey Department of Agriculture) https://www.nj.gov/agriculture/divisions/pi/prog/spottedlanternfly.html. (Pennsylvania Department of Agriculture) https://www.agriculture.pa.gov/Plants_Land_Water/PlantIndustry/Entomology/spotted_lanternfly/Pages/default.aspx. (Pennsylvania Extension – Penn State) https://extension.psu.edu/spotted-lanternfly. (New York State – Integrated Pest Management) https://cals.cornell.edu/new-york-state-integrated-pest-management/outreach-education/whats-bugging-you/spotted-lanternfly/spotted-lanternfly-management.

The Sweet Potato Weevil (SPW) is a very destructive pest of sweet potato in much of the tropical and subtropical regions of Asia, the Pacific, the Caribbean, the United States, Central and South America, and several African countries. Most of the host plants of SPW are in the genus Ipomoea, which includes both sweet potato and morning glory. Within the United States, SPW is present in parts of the following states: Alabama, Arkansas, Florida (widespread in Florida), Georgia, Hawaii, Louisiana, Mississippi, New Mexico, North Carolina, South Carolina, and Texas. It is a state quarantined pest in Tennessee, which helps to prevent the movement of SPW infested plant material into Tennessee and facilitates and ensures the movement of SPW free plant material within Tennessee and to other states from Tennessee. Adult SPW are not able to fly very far. However, they can easily be moved long distances on infested plants. TDA – Plant Certification Inspectors place pheromone traps in commercial growing/storage areas of Sweet Potato to detect any infestations of SPW. Localized SPW infestations in Tennessee during the 1980’s and one in 1995 were promptly eradicated through regulatory treatment, destruction of plant material, and prohibition of growing in the same area for 2 years. Worldwide, reported yield losses caused by SPW damage ranges from 5% to 80%. In areas of the United States that have SPW, it is necessary to utilize pheromone trapping, chemical controls, and cultural practices for successfully managing SPW in commercial sweet potato systems. SPW can damage sweet potatoes in the field and in storage. Larvae feeding on roots will cause yield loss and make the sweet potatoes have a bitter taste. Adults will feed on all parts of the plant. Adult SPW are small (6 mm long) and is a snout beetle that looks somewhat ant-like with a narrow head and thorax, long legs, and a long body. The head and abdomen are a metallic dark blue, and the thorax and legs are red. The long antennae are reddish-brown. In the deep south, there may be 5 or more generations per year. More information about SPW is available at the SPW website at Texas A & M https://texasinsects.tamu.edu/sweetpotato-weevil/; Florida Extension https://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/veg/potato/sweetpotato_weevil.htm; Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International – United Kingdom https://www.cabi.org/isc/datasheet/17408.

If you suspect any of these pests on your property please contact the State Entomologist at Cindy.Bilbrey@tn.gov.