DCS Access and Engagement Workgroup

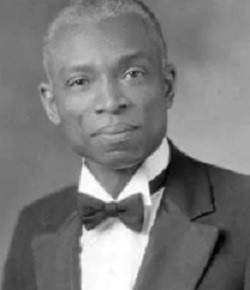

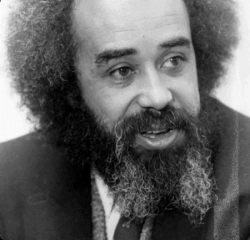

Reverend James Lawson

Rev. James Lawson was a Civil Rights Activist, college professor, and Methodist pastor. He dedicated his life to nonviolence and Racial Justice. He enrolled in Vanderbilt University Divinity School in 1958 and was later expelled for organizing the lunch counter sit-ins in Nashville. Rev. Lawson held training sessions prior to the sit-ins to prepare protesters and teach essential nonviolent techniques. Diane Nash (who was highlighted last month as part of the RJ Spotlight) was one of the many students that attended these sessions along with John Lewis, C.T. Vivian, Bernard Lafayette, and James Bevel. As a result of this critical training, the protests were successful, and Nashville became one of the first major Southern cities to desegregate lunch counters.

“We used the movement as a training ground,” Lawson told fellow civil rights figure Bill Barnes in a 2003 interview provided to the Nashville Scene by Robinson. “We continued workshops, we continued mass meetings, we continued teaching about nonviolence. We encouraged our people to take their personal experience on the front lines and appropriate and understand them in terms of themselves, their own growth, and the nonviolent strategy. I think that this was a better preparation than even I had known, though I think that what I did was at least very, very good for the time. And the net result was that it persuaded a number of people that this was a work that they could do, and it must be done. So we produced a quality of leadership that no other movement had produced. And that’s the other thing that Nashville people ought to take some pride in, and that is that we — that for the next decade or more, so many people out of the Nashville scene became some of the vanguard people, in Birmingham, the Freedom Ride campaign in ’61.”

Rev. Lawson recently transitioned on June 9, 2024, at the age of 95. There is a high school in Nashville named after him to commemorate his legacy.

Additional Resources:

James Lawson's Lasting Legacy

Boston University: A People's History

More Information

If you would like more information or are interested in joining the DCS Racial Justice Workgroup, please email ei_dcs.inservice@tn.gov.

Diane Nash

When Diane Nash was celebrated in Nashville, Tennessee on April 20, 2024, with the dedication of Diane Nash Plaza at the Historic Metro Courthouse, she was asked how she and the movement accomplished all they did. She answered simply something to the effect of by loving the other side. That’s staggering, allow it to soak in, “by loving the other side.” Diane grew up on the south side of Chicago and attended Fisk in the late 1950s. She was a member of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and was instrumental in desegregating Nashville’s lunch counters. Maybe you remember this question being asked of then-Mayor Ben West on the steps of the courthouse: “Do you think it’s wrong to discriminate against a person solely on the basis of his race or color?” This question was asked by Diane Nash on the same steps that now bear her name.

Diane spoke these words when addressing the crowd on the day of the dedication “People are never your enemy. Unjust political systems? They’re enemies. Unjust economic systems? They’re enemies. Mental and emotional illness? They are enemies. But not people. The first year that we had sit-ins in Nashville we targeted six restaurants and lunch counters. We had sit-ins and took them through the nonviolent process and successfully desegregated them. The second year, we targeted six more restaurants and lunch counters. That second year, one of the managers of a lunch counter that we had worked on and desegregated the first year took it upon himself to visit the owners and managers that we were working on that second year and he said to them, ‘Go ahead and desegregate. It’s a good thing to do. We haven’t lost any money.’ So, you see, he was an opponent the first year, and an ally the second year.

“It wasn’t he who was the enemy. It was his racism. Very often, if you target the person, you leave the real problem untouched.”

Her efforts and sacrifices along with so many others led to the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965. In the late 1960s, Nash returned to Chicago and became a public-school teacher while remaining involved in activism.

A famous quote from Diane: “There is a source of power in each of us that we don’t realize until we take responsibility.”

Next time you are in Nashville, take a few minutes to stop by the Diane Nash Plaza to honor this amazing and inspiring woman and to give thanks for all she has done for all of us. In the meantime, check out this rare footage obtained by the Nashville Banner which originally aired on NBC of Diane’s historic encounter on the courthouse steps.

National Day of Racial Healing: January 16, 2024

The National Day of Racial Healing is a time to contemplate our shared values and create the blueprint together for #HowWeHeal from the effects of racism. Launched in 2017, it is an opportunity to bring ALL people together in their common humanity and inspire collective action to create a more just and equitable world.

This annual observance is hosted by the W.K. Kellogg Foundation (WKKF) and was created with and builds on the work and learnings of the Truth, Racial Healing & Transformation (TRHT) community partners. Fundamental to this day is a clear understanding that racial healing is at the core of racial equity. This day is observed every year on the Tuesday following Martin Luther King, Jr. Day.

Racial healing is the experience shared by people when they speak openly and hear the truth about past wrongs and the negative impacts created by individual and systemic racism.

Racial healing helps to build trust among people and restores communities to wholeness, so they can work together on changing the systems and structures that affirm the inherent value of all people.

Racial equity is the condition where people of all races and ethnicities can live in a society where a person’s racial identity does not determine how they are treated nor predict life outcomes.

Achieving racial equity requires both systems transformation and racial healing.

Elizabeth Duff made history in Nashville by becoming the city’s first female bus operator and first African American female bus operator. Her legacy was honored at WeGo’s Central Transit Station downtown.

“She came at a time where there weren’t any women drivers,” said Nashville Metro Transit Authority (MTA) Board Chair Gail Williams. “She came at a time when there weren’t any Black women drivers.”

Soon after she was hired, three other women joined Nashville MTA and the transit authority soon realized they had to make some basic adjustments, like building bathrooms to accommodate their new employees. Breaking gender and color barriers also meant that Mrs. Duff endured sexism and racism, including those who questioned a woman’s ability to drive. But, that never stopped her.

In 2004, she was named Urban Driver of the Year by the Tennessee Public Transportation Association. Duff received the accolade because of her attendance, cooperation, courtesy and safety record. When asked by the newspaper The Tennessean, why she was drawn to driving, she said, “When you really drive, you feel the vehicle itself. You listen to the motor. You feel the road.”

Mrs. Duff retired in 2007 after more than three decades driving through the streets of Nashville.

Her son, Seneca Duff, followed in her footsteps, spending the last 18 years as a WeGo bus operator.

“My mom didn’t know about it at the time,” Seneca recalled. “It was a surprise. She was really excited that I got the job to work here.”

Along his route, Seneca has noticed the changes happening to the Central Transit Station.

“I watched them put up a letter here, a letter there, a letter here,” Seneca said. “I’m like, ‘They really putting it up,’ so it’s great.”

Elizabeth’s legacy is now cemented into the downtown station after the Metro Council approved the name change back in July 2022.

While Elizabeth’s family knows how special she is, they’re happy they can now share that with others as they ride past the Elizabeth Duff Transit Center. Elizabeth died in 2021 at the age of 72.

Resource information:

https://news.yahoo.com/nashville-wego-dedicate-downtown-transit-111348736.html

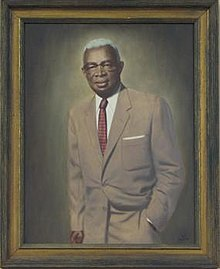

Dr. John Morton-Finney

Dr. John Morton-Finney was an accomplished lawyer, civil rights activist, and academic who accumulated eleven degrees over the course of his life. Born in Uniontown, Kentucky on June 25, 1889, Morton-Finney was one of seven children. His father, a former slave, and his mother, a free woman, taught their children the value of education. Though Morton-Finney was only 14 when his mother passed away, he shared her love for education and aspired to serve his country.

Before he began his academic pursuits, Morton-Finney joined the 24th Infantry Regiment of the United States Army. Morton-Finney fought in the Philippines. After being honorably discharged from the army in 1914, he earned his first degree in 1916 from Lincoln College in Jefferson City, Missouri, where he also met and fell in love with Pauline Ray. The two married, relocated to Indianapolis, Indiana, and together had one child, Gloria Ann Morton-Finney. To support his family, Morton-Finney taught at Crispus Attucks High School. Eventually, Morton-Finney assumed the role of dean of foreign languages at the high school and taught African American youth the importance of quality education for 47 years.

While working full time, Morton-Finney continued his education. He successfully completed all of the degree requirements to receive his Ph.D in Education at Indiana University, but he decided to turn down the degree. Afterward, he chose law and earned five degrees in the area including his first law degree from Lincoln College in 1935 and his J.D. from Indiana University in 1946 at the age of 57. He then embarked upon a lucrative career. After passing the Indiana bar in 1935, he entered private practice and eventually was allowed to argue cases before the Indiana Supreme Court. He also continued his education earning his last academic degree from Butler University at the age of 75. In 1972 John Morton-Finney, now 83, was admitted to practice law before the United States Supreme Court. At age 96, he earned his Doctor of Letters degree through Lincoln College (now University). He was inducted to the National Bar Association Hall of Fame in 1991 before retiring in 1996 at the age of 107 making him one of the longest practicing attorneys in United States history.

Dr. John Morton-Finney died on January 28, 1998 at the age of 108. He is buried at Crown Hill Cemetery in Indianapolis, Indiana along with his wife and daughter. He lived his life under the following principle: “I never stop studying. There’s always lots to learn. When you stop learning, that’s about the end of you.” His life-long legacy of learning lives on through the “Dr. John Morton-Finney Leadership Program” at Butler University for students who share his desire for quality education.

R.H. Boyd Publishing Corporation

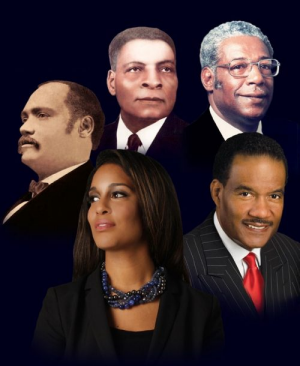

Five generations of Boyd family CEOs: Clockwise from left: R.H. Boyd, Henry Allen Boyd, T.B. Boyd Jr., T.B. Boyd III, and LaDonna Boyd. Photo courtesy The Union Tribune.

In the words of the fifth generation CEO, LaDonna Boyd, “The importance of the Black voice and narrative is unquantifiable, as this nation was built on the strength and perseverance of our ancestors. We have to tell our stories and write our dreams. As a publishing company, we are storytellers. We have the ability to shape the minds and experiences of the masses. As a Christian company, we have the significant responsibility and opportunity to draw people into the Kingdom through the written Word.”

R.H. Boyd Publishing Corporation Timeline

1843: Birth of Richard Henry Boyd in Mississippi as an enslaved person

1865-1870: After the Civil War and the Emancipation Proclamation freed enslaved people, Dick Gray moved to Texas as a freedman. He changed his name to Richard Henry “R.H.” Boyd in order to free himself of his slave master’s name. R.H. Boyd helped to organize the Texas Negro Baptist Convention. He also organized and served as pastor to several churches in Texas.

1870s: R.H. Boyd attended Bishop College in Marshall, Texas and worked tirelessly to organize churches and Freedmen Baptists across Texas.

1879: R.H. Boyd served as a district missionary and became Educational Secretary of the Texas Negro Baptist Convention and a moderator for the Central Baptist Association.

1896: R.H. Boyd founded the National Baptist Publishing Board (NBPB), now known as R.H. Boyd Publishing Corporation, in Nashville.

1904: R.H. Boyd helped found Citizens Savings Bank & Trust Company in Nashville.

1906: R.H. Boyd founded the National Baptist Congress Sunday School and Baptist Training Union Congress, now known as the National Baptist Congress.

1912: Dr. Henry Allen Boyd was among the influential business leaders responsible for locating Tennessee Agricultural and Industrial State Normal College for Negroes, now known as Tennessee State University, in Nashville.

1922: The death of Rev. Dr. R.H. Boyd. His son, Dr. Henry Allen Boyd (1876-1959), became the second generation to lead the company. He implemented new operational procedures and the company continued to flourish.

1934: NBPB was servicing 20,000 Sunday schools and 8,000 churches. It published more than 20 different hymnals and music books, a broad variety of Christian education materials, church supplies, and doctrinal resources for ministers and Christian workers.

1955: Dr. T.B. Boyd, Jr. (1917-1979) followed in his uncle’s footsteps by becoming a member of the company’s board of directors. After returning from military service in the United States Army in the mid-1940s, T.B. Boyd Jr. began his career with the company as a linotype operator in the composing room and became the understudy to Dr. Henry Allen Boyd.

1959: The death of Henry Allen Boyd. Dr. T.B. Boyd Jr. became President/CEO.

1960s: The publishing company was a leader in the forefront of the national civil rights and social agenda, giving strong support to the National Baptist Convention of America, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., and the Civil Rights Movement.

1974: NBPB relocated to current location on Centennial Boulevard

1979: The death of Dr. T.B. Boyd Jr. The board of directors appointed Dr. T. B. Boyd III as President and Chief Executive Officer. He became the youngest executive to hold the position in the 80-year history of the company. A year earlier, he had been elected to the Board of Directors of the Citizens Savings and Trust Company Bank. He became chairman of the board in 1982.

1996: NBPB reaches its centennial anniversary.

2000: NBPB becomes known as the R.H. Boyd Publishing Corporation. “We are very excited about this new and exciting publishing venture. The fact that we are paying homage to a man whose life and ministry created such positive impact in lives and communities across America, the Caribbean islands, and the Panama Canal alone, for over 100 years is befitting honor,” said Dr. T. B. Boyd III.

2012: R.H. Boyd Publishing Corporation begins distributing eBooks worldwide through distributors such as Amazon and Barnes & Noble.

2013: Technological upgrades and launch of new e-commerce platform.

2015: The R.H. Boyd Publishing Corporation’s Board of Directors unanimously voted LaDonna Boyd to serve as the Chief Operating Officer of the Corporation.

2017: Dr. T. B. Boyd III announced his retirement and transition to Chairman Emeritus status in October 2017. LaDonna Boyd is named as the President/CEO and Chairman of the Board of R.H. Boyd Publishing Corporation.

To learn more about the R.H. Boyd Corp, visit https://rhboyd.com/pages/about

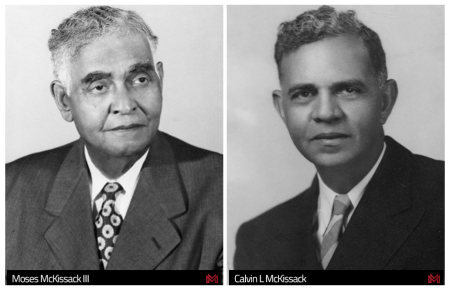

McKissack & McKissack

McKissack & McKissack is an American architecture, engineering, program management and construction firm. It is the oldest Black-owned architecture and construction company in the United States. The McKissack family helped build the city of Nashville.

The firm was founded by Moses McKissack III in 1905, who was later joined by his brother Calvin Lunsford McKissack to form the McKissack & McKissack partnership in 1922.

Gabriel “Moses” McKissack III was born on May 8, 1879, in Pulaski, Tennessee. His brother Calvin Lunsford McKissack was February 23, 1890. They had four brothers. Their father Gabriel Moses McKissack II, was a carpenter and builder; and their mother was Dolly Ann (née Maxwell). Their paternal grandfather Moses was from the Ashanti tribe (or Asante tribe, modern-day Ghana) and he was enslaved in 1790. Their grandfather was purchased by William McKissack, a white builder who taught him the building trade. When Moses was eventually granted his freedom, he began to sell his bricks. Moses McKissack II went on to become a master carpenter, and built the gingerbread finishes on the Maxwell House Hotel. Their grandfather married Mirian (1804–1865), who was Cherokee, and together they had fourteen children.

Moses McKissack attended Pulaski Colored High School. He apprenticed in construction drawings for 5 years under James Porter. He also attended classes at Springfield College in Springfield, Massachusetts and obtained architectural degrees through a correspondence course. In 1896, McKissack had moved to prepared construction drawings for B. F. McGrew and Pitman & Peterson. Calvin McKissack was educated at Fisk University in Nashville, which he attended from 1905 to 1909. Both brothers obtained architectural degrees through a correspondence course.

In 1927 the McKissacks designed the main library of Tennessee State University in Nashville. During the 1930s they received Works Progress Administration contracts for design of several public school buildings in the city, including Washington Junior High School on Nineteenth Avenue North (demolished), Pearl High School, and Ford Green School.

Around 1940, the firm began to expand outside Tennessee. Architectural licensing boards in some other states were skeptical of the qualifications of black architects. Tennessee authorities responded to their concerns with a statement that McKissack and McKissack was "...somewhat unique in the fact that it is one of the few Negro architectural firms in the country" and had "done some creditable work in Nashville, including several large school buildings running into a total cost of several hundred thousand dollars". The firm received licenses from Alabama in 1941 and from Georgia, South Carolina, Florida, and Mississippi in 1943. In 1942, the McKissack won a $5.7 million U.S. federal government contract to design and build Tuskegee Army Airfield, home to the Tuskegee Airmen's 99th Pursuit Squadron, in Tuskegee, Alabama. At the time, this was the largest federal contract ever awarded to a black-owned company. The successful on-time completion of the project brought positive attention to the company, including one writer's observation that "no racial friction occurred" in the work force of 1,600, of whom about three-fourths were black and one-fourth white. During the 1940s the firm also designed several public housing projects around the country, and Moses McKissack was appointed to President Franklin Roosevelt's White House Conference on Housing Problems. In 1942 the brothers were awarded the Spaulding Medal, recognizing the outstanding Negro business firm in the U.S.

Moses McKissack, III, died on December 12, 1952. Calvin became the president and general manager of the firm, remaining until his death in 1968. William DeBerry McKissack, the youngest son of Moses III, then succeeded his uncle as president of the firm. After suffering a stroke, he retired due to illness, and his wife, Leatrice Buchanan McKissack, became chief executive officer. In 2000, Cheryl McKissack Daniel purchased the company from her mother Leatrice, and became CEO and President. The move made her the company’s fifth-generation owner.

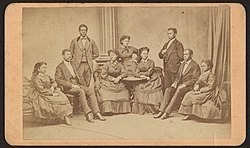

July 2023: Fisk Jubilee Singers

The Fisk Jubilee Singers are vocal artists and students at Fisk University in Nashville, TN, who sing and travel worldwide. The original Fisk Jubilee Singers introduced ‘slave songs’ to the world in 1871 and were instrumental in preserving this unique American musical tradition known today as Negro spirituals. They broke racial barriers in the US and abroad in the late 19th century and entertained Kings and Queens in Europe. At the same time, they raised money in support of their beloved school.

History

Fisk University opened in Nashville in 1866. The historically black college in Nashville, Tennessee, was founded by the American Missionary Association and local supporters after the end of the American Civil War to educate freedmen and other young African Americans. In 1871, the five-year-old university was facing serious financial difficulty. To avert bankruptcy and closure, Fisk's treasurer and music director, George Leonard White, gathered a nine-member student chorus, consisting of four black men (Isaac Dickerson, Ben Holmes, Greene Evans, Thomas Rutling) and five black women (Ella Sheppard, Maggie Porter, Minnie Tate, Jennie Jackson, Eliza Walker) to go on tour to earn money for the university. On October 6, 1871, the group of students, consisting of two quartets and a pianist, started their U.S. tour under White's direction. They first performed in Cincinnati, Ohio. Over the next 18 months, the group toured through Ohio, Pennsylvania, New York, Connecticut, Rhode Island, New Jersey, Massachusetts, Maryland, and Washington, D.C. Surprise, curiosity, and some hostility were the early audience response to these young black singers who did not perform in the traditional “minstrel fashion.”

Continued perseverance and beautiful voices began to change attitudes among the predominantly white audiences. Eventually skepticism was replaced by standing ovations and critical praise in reviews. The Jubilee Singers are credited with the early popularization of the Negro spiritual tradition among white and northern audiences in the late 19th century; many were previously unaware of its existence. At first the slave songs were never sung in public, according to Ella Sheppard; "they were sacred to our parents, who used them in their religious worship and shouted over them...It was only after many months that gradually our hearts were opened to the influence of these friends and we began to appreciate the wonderful beauty and power of our songs. After the rough start, the first United States tours eventually earned $40,000 for Fisk University.

In early 1872 the group performed at the World's Peace Jubilee and International Musical Festival in Boston, and they were invited to perform for President Ulysses S. Grant at the White House in March of that year. They gave a separate performance in Washington, D.C., for Vice President Schuyler Colfax and members of the U.S. Congress. They traveled next to New York, where they performed before enthusiastic audiences at preacher Henry Ward Beecher’s Plymouth Church in Brooklyn and at Steinway Hall in Manhattan. They garnered national attention and generous donations. Staying in the New York area for six weeks, by the time they returned to Nashville, they had raised the full $20,000 White had promised the university.

In 1873 the group grew to eleven members and toured Europe for the first time. Funds raised that year were used to construct the school’s first permanent building, Jubilee Hall. Today Jubilee Hall, designated a National Historic Landmark by the US Department of Interior in 1975, is one of the oldest structures on campus. The beautiful Victorian Gothic building houses a floor-to-ceiling portrait of the original Jubilee Singers, commissioned by Queen Victoria during the 1873 tour as a gift from England to Fisk.

Accomplishments

They broke racial barriers in the US and abroad in the late 19th century. In 1999, the Fisk Jubilee Singers were featured in the documentary Jubilee Singers: Sacrifice and Glory, which aired on PBS' American Experience. In July 2007, the Fisk Jubilee Singers went on a sacred journey to Ghana at the invitation of the U.S. Embassy. It was a history making event, as it was their first time visit to Ghana. In 2008, the Fisk Jubilee Singers were selected as a recipient of the 2008 National Medal of Arts, the nation's highest honor for artists and patrons of the arts. The award was presented by President George W. Bush and First Lady Laura Bush during a ceremony at the White House. In 2021, the Fisk Jubilee Singers won their first Grammy at the 63rd Annual Grammy Awards.

Jubilee Day

Fisk University commemorates the anniversary of the singers' first tour by celebrating Jubilee Day on October 6 each year. October 6, 1871 is the day the group left campus to tour.

To learn more about the Fisk Jubilee Singers click here https://fiskjubileesingers.org/about-the-singers/

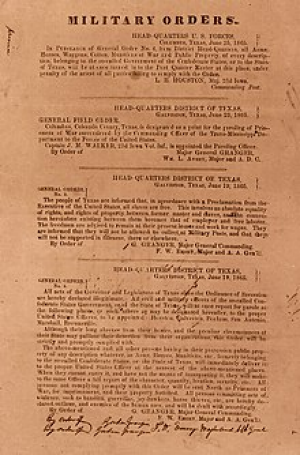

What is Juneteenth?

Juneteenth is a federal holiday in the United States commemorating the emancipation of enslaved African Americans. Deriving its name from combining "June" and "nineteenth", it is celebrated on the anniversary of the order, issued by Major General Gordon Granger on June 19, 1865, proclaiming freedom for enslaved people in Texas. And with those words, our country changed, this world changed. And, with bold and contentious decisions, we have continued to change – striving to make it better for all. Originating in Galveston, Texas, Juneteenth has since been observed annually in various parts of the United States, often broadly celebrating African-American culture. The day was first recognized as a federal holiday in 2021, when President Joe Biden signed the Juneteenth National Independence Day Act into law after the efforts of Lula Briggs Galloway, Opal Lee, and others. Juneteenth is now recognized as an official state holiday in Tennessee. On May 5, Governor Bill Lee signed a bill into a law that would recognize Juneteenth as an official holiday. The law will take effect in June of 2023.

History of Juneteenth

On “Freedom’s Eve,” or the eve of January 1, 1863, the first Watch Night services took place. On that night, enslaved and free African Americans gathered in churches and private homes all across the country awaiting news that the Emancipation Proclamation had taken effect. At the stroke of midnight, prayers were answered as all enslaved people in Confederate States were declared legally free. Union soldiers, many of whom were black, marched onto plantations and across cities in the south reading small copies of the Emancipation Proclamation spreading the news of freedom in Confederate States. Only through the Thirteenth Amendment did emancipation end slavery throughout the United States.

But not everyone in Confederate territory would immediately be free. Even though the Emancipation Proclamation was made effective in 1863, it could not be implemented in places still under Confederate control. As a result, in the westernmost Confederate state of Texas, enslaved people would not be free until much later. Freedom finally came on June 19, 1865, when some 2,000 Union troops arrived in Galveston Bay, Texas. The army announced that the more than 250,000 enslaved black people in the state, were free by executive decree. This day came to be known as "Juneteenth," by the newly freed people in Texas.

First Official Recognition

On January 1, 1980, Juneteenth became an official state holiday through the efforts of Al Edwards, an African American state legislator. The successful passage of this bill marked Juneteenth as the first emancipation celebration granted official state recognition. The same year, he hosted the inaugural Al Edwards prayer breakfast and commemorative celebration on the grounds of the 1859 home, Ashton Villa. As one of the few existing buildings from the Civil War era and popular in local myth and legend as the location of Major General Granger’s order, Edwards's annual celebration includes a local historian dressed as the Union general reading General Order No. 3 from the second story balcony of the home. The Emancipation Proclamation is also read and speeches are made. Representative Al Edwards died of natural causes April 29, 2020, at the age of 83, but the annual prayer breakfast and commemorative celebration continued at Ashton Villa, with the late legislator's son Jason Edwards speaking in his father’s place.

Celebrations and Festivities

The holiday is considered the "longest-running African-American holiday" and has been called "America's second Independence Day". Juneteenth is usually celebrated on the third Saturday in June. Early celebrations consisted of prayer and religious services, speeches, baseball, fishing, and rodeos. African Americans were often prohibited from using public facilities for their celebrations, so they were often held at churches or near water. Celebrations were also characterized by elaborate large meals and people wearing their best clothing. It was common for former slaves and their descendants to make a pilgrimage to Galveston.

Observances today include voter registration efforts, public readings of the Emancipation Proclamation, singing traditional songs such as "Swing Low, Sweet Chariot" and "Lift Every Voice and Sing", and reading of works by noted African-American writers, such as Ralph Ellison and Maya Angelou. Celebrations include picnics, rodeos, street fairs, cookouts, family reunions, park parties, historical reenactments, blues festivals and Miss Juneteenth contests. Red food and drinks are traditional during the celebrations, including red velvet cake and strawberry soda, with red meant to represent resilience and joy. The Mascogos, the descendants of Black Seminoles who have resided in Coahuila since 1852, also celebrate Juneteenth. Juneteenth is a day of education, reflection, cultural appreciation and hope for true liberation.

How to Celebrate and Commemorate

- Relax and reflect

- Educate yourself

- Patronize and support Black-owned businesses and restaurants

- Attend events and get involved in your community

- Read. You can start with the summer reading list curated by the National Museum of African American History and Culture, click here https://nmaahc.si.edu/visit/museum-store/juneteenth-reading-list

Juneteenth 2023 Observances in Tennessee

- June 16, 2023, at The Factory in Franklin, TN

- June 17, 2023, at Health Sciences Park in Memphis, TN

- June 17, 2023, at the Big Spring in Greeneville, TN

- June 17, 2023, at Freedom Run & Walk at Hubert Fry Center in Chattanooga, TN

- June 19, 2023, at Fort Negley in Nashville, TN

- June 19, 2023, at Shelby Bottoms Greenway, Nashville, TN

For other observances in the State of Tennessee, google Juneteenth & your specific city.

Z. Alexander Looby

Zephaniah Alexander Looby was born on April 8, 1899, in Antigua, British West Indies. His father was John Alexander Looby and his mother, Grace Elizabeth Joseph. When he was five, his mother died while giving birth to a sibling. His father died when Looby was a teenager. He moved to the United States in 1914 as an orphan when he was fifteen years old.

Looby attended Howard University as an undergraduate, and became a member of the Omega Psi Phi fraternity. He graduated with a bachelor's degree in 1922. He went on to earn a law degree in 1925 from Columbia University in New York City, and a doctorate in jurisprudence from New York University in 1926. That same year he became a naturalized citizen of the United States.

Looby came to Nashville, Tennessee in 1926 to work as an assistant professor of economics at Fisk University. July 1928, he passed the Tennessee bar exam and opened his own practice in Memphis for three years. In 1934 he married Grafta Mosby, a Memphis schoolteacher. Looby returned to Nashville and helped found the Kent College for Law.

Looby was part of the defense team organized by the NAACP for black men charged in the Columbia race riot of 1946. Looby worked with white attorney Maurice Weaver from Chattanooga and Thurgood Marshall of the Legal Defense and Educational Fund of the NAACP; the latter led the defense team. They won acquittals for 24 of the 25 men charged, and the last had his charges reduced, in the aftermath of the first major racial confrontation in the United States after World War II.

As a young state senator in Nashville's fifth ward, Ben West pushed for a charter reform in 1950 to allow local residents to elect city council members from single-member districts rather than through at-large voting. The latter system favored the white majority in the city and made it difficult for the sizeable African-American minority ever to elect candidates of their choice. With the change, African Americans began to elect some candidates. At that time, many black voters were still disenfranchised since the state had passed laws in the late 1880s to charge poll taxes and make voter registration and voting difficult.

After the change to the charter, in May 1951 Looby was elected to the Nashville City Council, along with another lawyer, Robert Lillard. They were the first African Americans to be elected to the council since 1911. In 1953, the state passed a constitutional amendment to repeal the poll tax. This led to increased numbers of African Americans registering to vote statewide.

After the United States Supreme Court ruled in Brown v. Board of Education (1954) that segregation of public schools was unconstitutional, Looby filed a suit in Nashville on behalf of A.Z. Kelley. His son had been denied admission to a traditionally white school. Looby is credited with beginning the school desegregation movement in Nashville.

Beginning in February 1960, councilman Looby defended the students arrested in the Nashville sit-ins to achieve integration of public places. His law associates Avon Nyanza Williams and Robert E. Lillard also were part of the defense team. As a result of Looby's support of the students, his house was dynamited by segregationists on April 19, 1960. The house was nearly destroyed by the powerful bomb, which also blew out 140 windows at nearby Meharry Medical College, resulting in minor injuries to students. Neither Looby nor his wife, Grafta Mosby Looby, were harmed in the bombing.

Afterward students from Fisk University led 2500 protesters on a silent walk to city hall, where they confronted Mayor Ben West. Diane Nash asked him, "Do you feel it is wrong to discriminate against a person solely on the basis of their race or color?" West said "yes,' later explaining, "It was a moral question – one that a man had to answer, not a politician." By May of that year, lunch counters in Nashville were desegregated. By October, Looby and his team gained dismissal of the charges against 91 students "for conspiracy to disrupt trade and commerce."

Looby died on March 24, 1972. He is buried in Greenwood Cemetery in Nashville.

In 1976, the city government of Nashville named a new library and community center in Looby's honor. In 1978, the James C. Napier Lawyers Association changed its name to the Napier-Looby Bar Association, in honor of Looby and his accomplishments. In 1982, the Nashville Bar Association posthumously awarded Looby membership; it had rejected him on racial grounds when he applied in the 1950s. Looby has a Tennessee Historical Commission marker erected in his honor.

To see pictures of Z Alexander Looby over the years click here:

To learn more about the Columbia race riot click here:

https://tennesseeencyclopedia.net/entries/columbia-race-riot-1946/

Amanda Hughes Patton North was born in 1913 in Franklin, Tennessee to Robert and Maggie Patton. She later married Harvey J North and together they had 2 daughters, Maggie Brown and Dorothy Jackson, who both taught for more than 40 years.

Mrs. North began her teaching career in 1934, straight out of high school. During segregation, Thompson’s Station was a one-room schoolhouse for first- through eighth-grade school for Black and African American students. She taught during the school year and went to college during the summer until she graduated from Tennessee A & I State College, which is now Tennessee State University.

While teaching, Mrs. North realized that the 20-cent lunch fee was more than some of her students could afford. She organized community suppers to help cover the costs. She recognized that some of her students lived too far to walk, so she drove to pick them up so they could achieve an education.

Mrs. North’s teaching career went on to span 40 years in Williamson County. She became the principal at Thompson station school and Evergreen school in Spring Hill. Later, she taught adult education at Natchez High School in Franklin. She was Williamson County’s first Black principal. In addition, she was a member of the Williamson County Negro Teachers Association.

“In the ’40s, for a Black woman to ascend to a leadership position speaks to [her] intellect, the passion for education, the love for children and the respect the community must have had for her because there were so many barriers for women alone on top of the segregation of the schools at the time too,” Eliot Mitchell said (Third District). “I am excited we can recognize this lady by naming a school after her, and I am excited her family is here tonight to see that happen.”

She was a beloved member of the community, and, though she passed away in 2011, her impact is still felt. North began a legacy of educators, with a number of her children and grandchildren going into the noble profession. Her legacy and name will live on. Amanda H. North will be the namesake for a new elementary school in Spring Hill, Tennessee.

Mrs. North was paternal great-aunt of Ronlanda Foley, B.S, RN, Mid-Cumberland Regional DCS Nurse Consultant. We are proud to honor such an amazing family.

Learn more at:

Dorothy Height

Dorothy Irene Height was born on March 24th, 1912 in Richmond, Virginia. Her family later moved to Rankin, Pennsylvania where she excelled as a student. Height eventually received a scholarship to attend college. In 1929, she was admitted to Barnard College but was not allowed to attend because the school had an unwritten policy of admitting only two black students per year. Instead, Height went on to graduate from New York University where she received a bachelor’s in education and master’s in psychology. She pursued further postgraduate work at Columbia University and the New York School of Social Work.

Her first job was as a social worker in Harlem, New York. She later joined the staff of the Harlem Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA). In no time, Height became a leader in the local organization. She created diverse programs and pushed the organization to integrate YWCA facilities nationwide.

Height focused on ending the lynching of African Americans and restructuring the criminal justice system. In 1957, she became the fourth president of the National Council of Negro Women. Under her leadership, the NCNW supported voter registration in the South. The NCNW also financially aided several civil rights activists throughout the country. Height was president of NCNW for 40 years.

Height’s prominence in the Civil Rights Movement and unmatched knowledge in organizing, meant she was regularly called to give advice on political issues. Eleanor Roosevelt, Dwight D. Eisenhower, and Lyndon B. Johnson often sought her counsel. In 1963, Height, along with other civil rights activists organized the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. Although she played a role in the march, she was not invited to speak. In fact, originally no women were included on the program at all. Height and Anna Arnold Hedgeman persuaded the other organizers to allow a woman to speak. Despite the apparent gender discrimination in the Civil Rights Movement, Height continued working on the front lines.

In addition to her work in the United States, Height traveled extensively. She served as a visiting professor at the University of Delhi, India and with the Black Women’s Federation of South Africa. For all her efforts during the Civil Rights Movement, Height was awarded and recognized by many organizations. In 1989, she received the Citizens Medal Award from President Ronald Reagan and in 2004, Height was honored with the Congressional Gold Medal. The same year, Height was inducted into the Democracy Hall of Fame International. She also received an estimated 24 honorary degrees. On April 20th, 2010, Height passed away at the age of 98. Her funeral was held at Washington National Cathedral.

Click on the link to learn more about The Dorothy I. Height Global Leadership Academy

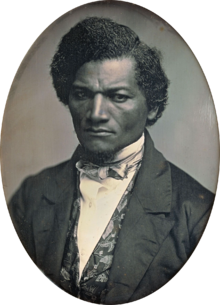

Frederick Douglass

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was born into slavery on the Eastern Shore of Maryland in February 1818. Though the exact date of his birth is unknown, he chose to celebrate February 14 as his birthday, remembering that his mother called him her "Little Valentine." He had a difficult family life. He barely knew his mother, who lived on a different plantation and died when he was a young child. He never discovered the identity of his father. When he turned eight years old, his slaveowner hired him out to work as a body servant in Baltimore. Although most people didn’t want enslaved people to learn to read, the wife of the man Douglass worked for taught him but later stopped. Douglass continued, secretly, to teach himself to read and write. He later often said, "knowledge is the pathway from slavery to freedom." As Douglass began to read newspapers, pamphlets, political materials, and books of every description, this new realm of thought led him to question and condemn the institution of slavery.

When Frederick was fifteen, his slaveowner sent him back to the Eastern Shore to labor as a fieldhand. Frederick rebelled intensely. He educated other slaves, physically fought back against a "slave-breaker," and plotted an unsuccessful escape. Frustrated, his slaveowner returned him to Baltimore. This time, Frederick met a young free black woman named Anna Murray, who agreed to help him escape. On September 3, 1838, he disguised himself as a sailor and boarded a northbound train, using money from Anna to pay for his ticket. In less than 24 hours, Frederick arrived in New York City and declared himself free. He had successfully escaped from slavery. He married Anna Murray Douglass on September 15, 1838, just eleven days after Douglass had reached New York. They decided that New York City was not a safe place for Frederick to remain as a fugitive, so they settled in New Bedford, Massachusetts. There, they adopted the last name "Douglass" and they started their family, which would eventually grow to include five children: Rosetta, Lewis, Frederick, Charles, and Annie.

He continued to read as much as he could. He became a licensed preacher in 1839, which helped him to hone his oratorical skills. He held various positions, including steward, Sunday-school superintendent, and sexton. In 1840, Douglass delivered a speech in Elmira, New York, then a station on the Underground Railroad, in which a black congregation would form years later, becoming the region's largest church by 1940. While living in Massachusetts, he spoke at a meeting of abolitionists. He told them about his life as an enslaved person. He was such an amazing speaker that he started traveling all over the northern states, trying to convince large groups of people to end the practice.

Douglass engaged in early protest against segregated transportation. In September 1841, at Lynn Central Square station, Douglass and friend James N. Buffum were thrown off an Eastern Railroad train because Douglass refused to sit in the segregated railroad coach.

In 1843, Douglass joined other speakers in the American Anti-Slavery Society's "Hundred Conventions" project, a six-month tour at meeting halls throughout the eastern and midwestern United States. During this tour, slavery supporters frequently accosted Douglass. At a lecture in Pendleton, Indiana, an angry mob chased and beat Douglass before a local Quaker family, the Hardys, rescued him. His hand was broken in the attack; it healed improperly and bothered him for the rest of his life. A stone marker in Falls Park in the Pendleton Historic District commemorates this event.

Douglass's fame as an orator increased as he traveled. Still, some of his audiences suspected he was not truly a fugitive slave. In 1845, he published his first autobiography, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, to lay those doubts to rest. The narrative gave a clear record of names and places from his enslavement. To avoid being captured and re-enslaved, Douglass traveled overseas. For almost two years, he gave speeches and sold copies of his narrative in England, Ireland, and Scotland. When abolitionists offered to purchase his freedom, Douglass accepted and returned home to the United States legally free. He relocated Anna and their children to Rochester, New York. After returning to the U.S. in 1847, using £500 (equivalent to $48,612 in 2021) given to him by English supporters, Douglass started publishing his first abolitionist newspaper, the North Star.

In 1848, Douglass was the only black person to attend the Seneca Falls Convention, the first women's rights convention, in upstate New York. After Douglass's powerful words, the attendees passed the resolution asking for women’s suffrage.

Like many abolitionists, Douglass believed that education would be crucial for African Americans to improve their lives; he was an early advocate for school desegregation. In the 1850s, Douglass observed that New York's facilities and instruction for African-American children were vastly inferior to those for European Americans. Douglass called for court action to open all schools to all children. He said that full inclusion within the educational system was a more pressing need for African Americans than political issues such as suffrage.

Douglass and the abolitionists argued that because the aim of the Civil War was to end slavery, African Americans should be allowed to engage in the fight for their freedom. Douglass publicized this view in his newspapers and several speeches. After Lincoln had finally allowed black soldiers to serve in the Union army, Douglass helped the recruitment efforts, publishing his famous broadside Men of Color to Arms! on March 21, 1863.

After the Civil War, Douglass continued to work for equality for African Americans and women. Due to his prominence and activism during the war, Douglass received several political appointments. He served as president of the Reconstruction-era Freedman's Savings Bank.

Throughout the Reconstruction era, Douglass continued speaking, emphasizing the importance of work, voting rights and actual exercise of suffrage. His speeches for the twenty-five years following the war emphasized work to counter the racism that was then prevalent in unions. In a November 15, 1867, speech he said "A man's rights rest in three boxes. The ballot box, jury box and the cartridge box. Let no man be kept from the ballot box because of his color. Let no woman be kept from the ballot box because of her sex."

When Republican Rutherford B. Hayes was elected president, he named Douglass as United States Marshal for the District of Columbia, the first person of color to be so named. The Senate voted to confirm him on March 17, 1877. Douglass accepted the appointment, which helped assure his family's financial security.

At the 1888 Republican National Convention, Douglass became the first African American to receive a vote for President of the United States in a major party's roll call vote. He was appointed as United States Minister Resident to Haiti in 1889 by President Harrison.

In 1892, Douglass constructed rental housing for blacks, now known as Douglass Place, in the Fells Point area of Baltimore. The complex still exists, and in 2003 was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

The most influential African American of the nineteenth century, Douglass made a career of agitating the American conscience. He spoke and wrote on behalf of a variety of reform causes: women's rights, temperance, peace, land reform, free public education, and the abolition of capital punishment. But he devoted the bulk of his time, immense talent, and boundless energy to ending slavery and gaining equal rights for African Americans. These were the central concerns of his long reform career. Douglass understood that the struggle for emancipation and equality demanded forceful, persistent, and unyielding agitation. And he recognized that African Americans must play a conspicuous role in that struggle. Less than a month before his death, when a young black man solicited his advice to an African American just starting out in the world, Douglass replied without hesitation: ″Agitate! Agitate! Agitate!″

On February 20, 1895, Douglass attended a meeting of the National Council of Women in Washington, D.C. During that meeting, he was brought to the platform and received a standing ovation. Shortly after he returned home, Douglass died of a massive heart attack. He is buried at Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester, New York.

Douglass’s legacy lives on in his writings, speeches and honors. His brilliant words and brave actions continue to shape the ways that we think about race, democracy, and the meaning of freedom.

Learn more at https://frederickdouglassinstitute.org/

Dr. Thelma Bryant-Davis

Growing up in Baltimore, the daughter of influential pastors, Thema Bryant learned something early on: A call to the family’s house was usually a call for help.

While an undergraduate at Duke University, Thema went home to Baltimore on a school break and was sexually assaulted by a family friend. A psychology major at that point, she got a work-study position at a rape crisis center near Duke where she learned to understand and harness what she calls her “special compassion” for survivors of sexual trauma. She soon began honing her specialty based on a growing awareness that trauma can be caused and experienced differently by people from different socioeconomic statuses, races, genders, and sexual orientations.

Decades later, Thema Bryant is Dr. Thema Bryant-Davis, a Duke PhD, president-elect of the American Psychological Association, ordained minister, psychologist, Pepperdine University professor, author, editor, dancer, poet—and a very new kind of listener.

Dr. Thema Bryant completed her doctorate in Clinical Psychology at Duke University and her post-doctoral training at Harvard Medical Center’s Victims of Violence Program. Upon graduating, she became the Coordinator of the Princeton University SHARE Program, which provides intervention and prevention programming to combat sexual assault, sexual harassment, and harassment based on sexual orientation. She is currently a tenured professor of psychology in the Graduate School of Education and Psychology at Pepperdine University, where she directs the Culture and Trauma Research Laboratory. Her clinical and research interests center on interpersonal trauma and the societal trauma of oppression. She is a past president of the Society for the Psychology of Women and a past APA representative to the United Nations. Dr. Thema also served on the APA Committee on International Relations in Psychology and the Committee on Women in Psychology.

Her clinical and research interests center on interpersonal trauma and the societal trauma of oppression. In 2007 the American Psychological Association awarded her the Emerging Leader of Women in Psychology Award for her scholarship and clinical work on violence against women. In addition, she was awarded the Sarah Allen Research on the Status of Black Women Award. Her research expertise is in the cultural context of trauma, particularly child abuse, partner abuse, sexual assault, and the societal trauma of racism. She directs the Culture and Trauma Research Lab which studies the intersection of cultural context and trauma recovery. Dr. Bryant’s work has been highlighted on BET and PBS, as well as in the Trenton Times, Herald Sun, and Boston Globe.

Dr. Bryant is author of the book Thriving in the Wake of Trauma: A Multicultural Guide and is published in the journals The Counseling Psychologist, Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, and Trauma, Violence, and Abuse. Dr. Bryant serves on the Editorial Board for the journal Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. Her book chapters can be found in the books The Complete Guide to Mental Health for Women, The Psychology of Racism and Discrimination, The Encyclopedia of Psychological Trauma, and Featuring Females; Feminist Analyses of the Media. Dr. Thema recently just published another book entitled “Home Coming: Overcome Fear and Trauma to Reclaim Your Whole Authentic Self” in 2022. In addition, she hosts a podcast entitled “The Homecoming Podcast”. Dr. Thema has been featured in various TV, newspaper, articles, and media outlets which can be found here.

On a global level, Dr. Bryant was previously selected as an American Psychological Association representative to the United Nations where she provided education, advocacy, and monitoring of Member States' mental health policies for three years, and served as the Global and International Issues Chairperson for the Society for the Psychology of Women. She is also a past president of the Society for the Psychology of Women and also served on the APA Committee on International Relations in Psychology and the Committee on Women in Psychology.

The American Psychological Association honored her for Distinguished Early Career Contributions to Psychology in the Public Interest in 2013. The Institute of Violence, Abuse and Trauma honored her with their media award for the film Psychology of Human Trafficking in 2016 and the Institute honored her with the Donald Fridley Memorial Award for excellence in mentoring in the field of trauma in 2018. The California Psychological Association honored her for Distinguished Scientific Achievement in Psychology in 2015. She is the editor of the APA text Multicultural Feminist Therapy: Helping Adolescent Girls of Color to Thrive. She is one of the foundational scholars on the topic of the trauma of racism and in 2020, she gave an invited keynote address on the topic at APA. In 2020, the International Division of APA honored her for her International Contributions to the Study of Gender and Women for her work in Africa and the Diaspora. Dr. Thema has raised public awareness regarding mental health by extending the reach of psychology beyond the academy and private therapy office through community programming and media engagement, including but not limited to Headline News, National Public Radio, and CNN.

Bryan Stevenson

Bryan Stevenson is the founder and Executive Director of the Equal Justice Initiative, a human rights organization in Montgomery, Alabama. Under his leadership, EJI has won major legal challenges eliminating excessive and unfair sentencing, exonerating innocent death row prisoners, confronting abuse of the incarcerated and the mentally ill, and aiding children prosecuted as adults.

Mr. Stevenson has argued and won multiple cases at the United States Supreme Court, including a 2019 ruling protecting condemned prisoners who suffer from dementia and a landmark 2012 ruling that banned mandatory life-imprisonment-without-parole sentences for all children 17 or younger. Mr. Stevenson and his staff have won reversals, relief, or release from prison for over 135 wrongly condemned prisoners on death row and won relief for hundreds of others wrongly convicted or unfairly sentenced.

Mr. Stevenson has initiated major new anti-poverty and anti-discrimination efforts that challenge inequality in America. He led the creation of two highly acclaimed cultural sites which opened in 2018: the Legacy Museum and the National Memorial for Peace and Justice. These new national landmark institutions chronicle the legacy of slavery, lynching, and racial segregation, and the connection to mass incarceration and contemporary issues of racial bias.

Mr. Stevenson’s work has won him numerous awards, including the prestigious MacArthur Foundation “Genius” Prize; the ABA Medal, the American Bar Association’s highest honor; the National Medal of Liberty from the American Civil Liberties Union after he was nominated by United States Supreme Court Justice John Stevens; the Public Interest Lawyer of the Year by the National Association of Public Interest Lawyers; and the Olaf Palme Prize in Stockholm, Sweden, for international human rights. In 2002, he received the Alabama State Bar Commissioners Award. In 2003, the SALT Human Rights Award was presented to Mr. Stevenson by the Society of American Law Teachers. In 2004, he received the Award for Courageous Advocacy from the American College of Trial Lawyers and also the Lawyer for the People Award from the National Lawyers Guild. In 2006, New York University presented Mr. Stevenson with its Distinguished Teaching Award. Mr. Stevenson won the Gruber Foundation International Justice Prize and was awarded the NAACP William Robert Ming Advocacy Award, the National Legal Aid & Defender Association Lifetime Achievement Award, the Ford Foundation Visionaries Award, and the Roosevelt Institute Franklin D. Roosevelt Freedom from Fear Award. In 2012, Mr. Stevenson received the American Psychiatric Association Human Rights Award, the Birmingham Civil Rights Institute Fred L. Shuttlesworth Award, and the Smithsonian Magazine American Ingenuity Award in Social Progress. Mr. Stevenson was inducted into the American Academy of Arts and Science in 2014 and won the Lannan Cultural Freedom Prize. In 2015, he was named to the Time 100 list recognizing the world’s most influential people. In 2016, he received the American Bar Association’s Thurgood Marshall Award. He was named in Fortune’s 2016 and 2017 World’s Greatest Leaders list. He received the Martin Luther King Jr. Nonviolent Peace Prize from the King Center in Atlanta in 2018.

Mr. Stevenson has received over 40 honorary doctoral degrees, including degrees from Harvard, Yale, Princeton, the University of Pennsylvania, and Oxford University. He is the author of the critically acclaimed New York Times bestseller, Just Mercy, which was named by Time Magazine as one of the 10 Best Books of Nonfiction for 2014 and has been awarded several honors, including the American Library Association’s Carnegie Medal for best nonfiction book of 2015 and a 2015 NAACP Image Award. Just Mercy was recently adapted as a major motion picture. He is a graduate of the Harvard Law School and the Harvard School of Government.

The Equal Justice Initiative website: https://eji.org/

National Native American Heritage Month

On August 3, 1990, President of the United States George H. W. Bush declared the month of November as National American Indian Heritage Month, thereafter commonly referred to as Native American Heritage Month. The bill read in part that "the President has authorized and requested to call upon Federal, State and local Governments, groups and organizations and the people of the United States to observe such month with appropriate programs, ceremonies and activities". This commemorative month aims to provide a platform for Native people in the United States of America to share their culture, traditions, music, crafts, dance, and ways and concepts of life. This gives Native people the opportunity to express to their community, both city, county and state officials their concerns and solutions for building bridges of understanding and friendship in their local area. Federal Agencies are encouraged to provide educational programs for their employees regarding Native American history, rights, culture and contemporary issues, to better assist them in their jobs and for overall awareness.

Jerry Chris Elliott High Eagle

This landmark bill honoring America's tribal people represented a major step in the establishment of this celebration which began in 1976 when a Cherokee/Osage Indian named Jerry C. Elliott High Eagle authored Native American Awareness Week legislation, the first historical week of recognition in the nation for native peoples. This led to 1986 with then President Ronald Reagan proclaiming November 23–30, 1986, as "American Indian Week".

Jerry Chris Elliott High Eagle was born in 1943 in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. From an early age he had a vision of assisting astronauts to get to the moon. After graduating from Northwest Classen High School, he was accepted into the University of Oklahoma at the age of 18. While in university, he faced a degree of culture shock, facing disrespect and misunderstandings towards him as a Native American. He received a degree in physics with a minor in mathematics, April, 1966, being the first indigenous native to obtain one from the University of Oklahoma, Department of Physics.

Elliott joined NASA in April 1966 as a flight mission operations engineer, serving at the Mission Control Center in Houston, Texas. He was Program Staff Engineer at the NASA Headquarters in Washington, DC during the Apollo-Soyuz Program. He served as a Senior Technical Manager in the Management Integration Office of the Space Station's Program Office. Elliott and his team provided ground support equipment and space hardware for Skylab, the United States' first space station.

While at NASA, Elliott pushed for furthering telecommunications infrastructure between reservations. Implemented the American Indian Telecommunications Satellite Demonstration Project linked the All-Indian Pueblo Council and the Crow Indian Reservation with the federal government at Washington, D.C. His testimony before Congress culminated in the establishment in the First Americans Commission for Telecommunications (FACT).

During the Apollo program he held several important management and leadership positions. He is most known for his contributions as the lead retrofire officer during Apollo 13, where his actions saved the lives of the three astronauts on board. Elliott's work awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the highest civilian honor awarded by the President of the United States.

Arthur Caswell Parker

Prior to Elliott, one of the very first proponents of an American Indian Day was Dr. Arthur C. Parker. Parker was born in 1881 on the Cattaraugus Reservation of the Seneca Nation of New York in western New York. He was the son of Frederick Ely Parker and his wife Geneva Hortenese Griswold, of Scots-English-American descent, who taught school on the reservation. Parker started his formal education on the reservation, but in 1892, his family moved to White Plains, New York. He entered public school at around age 11 and graduated from high school in 1897. Before going on to college, he spent considerable time at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City, where he was special assistant archaeologist 1901–1902.

He was field archaeologist at the Peabody Museum in 1903; beginning 1906, he was archaeologist of the New York State Museum. In 1904, Parker was given a two-year position as ethnologist at the New York State Library, part of the New York State Education Department, and collected cultural data on the New York Iroquois. Then in 1906, he took a position as the first archaeologist at the New York State Museum.

In 1911, together with the Native American physician Charles A. Eastman and others, he founded the Society of American Indians to help educate the public about Native Americans. During the 1911 New York State Capitol fire Parker entered the building while it was ablaze, and made his way up to the 4th floor in an effort to save priceless historical artifacts. He brought a tomahawk, which had been passed down through the generations in his family, and began smashing display cases, saving as many items as he could. Of the approximately five hundred Iroquois artifacts in the museum he was able to rescue about fifty of them before the spreading fire made any further salvage efforts impossible.

He persuaded the Boy Scouts of America to set aside a day for the “First Americans” and for three years they adopted such a day. In 1915, the annual Congress of the American Indian Association meeting in Lawrence, Kans., formally approved a plan concerning American Indian Day. It directed its president, Rev. Sherman Coolidge, an Arapahoe, to call upon the country to observe such a day. Coolidge issued a proclamation on Sept. 28, 1915, which declared the second Saturday of each May as an American Indian Day and contained the first formal appeal for recognition of Indians as citizens. The year before this proclamation was issued, Red Fox James, a Blackfoot Indian, rode horseback from state to state seeking approval for a day to honor Indians. On December 14, 1915, he presented the endorsements of 24 state governments at the White House.

From 1915 to 1920, he was the editor of the society's American Indian Magazine. In 1916, he was awarded the Cornplanter Medal.

In 1925 Parker became director of the Rochester Museum of Arts and Sciences, where he developed the museum holdings and its research in the emerging fields of anthropology, natural history, geology, biology, history and industry of the Genesee Region. During the 1930s and the Great Depression, he also directed the WPA-funded Indian Arts Project, which was sponsored by the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration.

In 1935, Parker was elected the first President of the Society for American Archaeology. In 1944, Parker helped found the National Congress of American Indians. After retiring from directing the Rochester museum in 1946, Parker became very active in Indian affairs. He moved to Nunda-wah-oh, near present-day Naples, New York, where he felt his ancestors had lived. There he overlooked Canandaigua Lake. He died there on New Year's Day, 1955, aged 73.

General Benjamin Oliver Davis Sr.

Davis was born in Washington, D.C., the third child of Louis P. H. Davis and Henrietta Davis. It is believed he was born May 28, 1880. However, the birth date that appears on Davis's gravestone at Arlington National Cemetery is July 1, 1877, the date he provided to the Army to enlist without the permission of his parents. Davis attended M Street High School in Washington, where he participated in the cadet program.

He entered military service on July 13, 1898, during the War with Spain as a temporary first lieutenant of the 8th United States Volunteer Infantry. He was mustered out on March 6, 1899, and on June 18, 1899, he enlisted as a private in Troop I, 9th Cavalry, of the Regular Army. He then served as corporal and squadron sergeant major, and on February 2, 1901, he was commissioned a second lieutenant of Cavalry in the Regular Army and was posted overseas to serve in the Philippine–American War. Troop F returned to the US in August 1902. Davis was then stationed at Fort Washakie, Wyoming, where he also served for several months with Troop M. In September 1905, he was assigned to the traditionally Black Wilberforce College in Ohio as Professor of Military Science and Tactics, a post that he filled for four years.

In November 1909, shortly after being ordered to Regimental Headquarters, 9th Cavalry, Davis was reassigned for duty to Liberia. He left the United States for Liberia in April 1910, and served as a military attaché reporting on Liberia's military forces until October 1911. He returned to the United States in November 1911. In January 1912, Davis was assigned to Troop I, 9th Cavalry, stationed at Fort D. A. Russell, Wyoming. In 1913, the 9th Cavalry was assigned to patrol the Mexican-United States border.

In February 1915, Davis was again assigned to Wilberforce College as Professor of Military Science and Tactics. From 1917 to 1920, Davis was assigned to the 9th Cavalry at Fort Stotsenburg, Philippine Islands, as supply officer, commander of the 3rd Squadron, and then of the 1st Squadron. He reached the temporary rank of lieutenant colonel but returned to the United States in March 1920 with the rank of captain.

Davis was assigned to the traditionally Black Tuskegee Institute (now Tuskegee University) in Tuskegee, Alabama, as the professor of military science and tactics from 1920 to 1924. He then served for five years as an instructor with 2nd Battalion, 372nd Regiment, Ohio National Guard, in Cleveland, Ohio. In September 1929, Davis returned to Wilberforce as a professor of military science and tactics. He was assigned to the Tuskegee Institute in the early part of 1931 and remained there for six years as a professor of military science and tactics. During the summer months of 1930 to 1933, Davis escorted pilgrimages of World War I Gold Star mothers and widows to the burial places of their loved ones in Europe.

In August 1937, Davis returned to Wilberforce University as a professor of military science and tactics. Davis was assigned to the 369th Regiment, New York National Guard, during the summer of 1938, and took command of the regiment a short time later. Davis was promoted to brigadier general on October 25, 1940, becoming the first African-American general officer in the United States Army.

Davis became commanding general of the 4th Cavalry Brigade, 2nd Cavalry Division at Fort Riley, Kansas, in January 1941. About six months later, he was assigned to Washington, D.C. as an assistant in the Office of the Inspector General. While serving in the Office of the Inspector General, Davis also served on the Advisory Committee on Negro Troop Policies. From 1941 to 1944, Davis conducted inspection tours of African-American soldiers in the United States Army. From September to November 1942 and again from July to November 1944, Davis made inspection tours of African-American soldiers stationed in Europe.

On November 10, 1944, Davis was reassigned to work under Lieutenant General John C. H. Lee as special assistant to the commanding general, Communications Zone, European Theater of Operations. He served with the General Inspectorate Section, European Theater of Operation (later the Office of the Inspector General in Europe) from January through May 1945. While serving in the European Theater of Operations, Davis was influential in the proposed policy of integration using replacement units.

After serving in the European Theater of Operations for more than a year, Davis returned to Washington, D.C. as an assistant to the Inspector General. In 1947 he was assigned special assistant to the Secretary of the Army. In this capacity, he was again sent to Liberia in July 1947 as a representative of the United States for the African country's centennial celebration.

On July 20, 1948, after fifty years of military service, Davis retired in a public ceremony with President Harry S. Truman presiding. Six days later on July 26, 1948, President Truman issued Executive Order 9981 which abolished racial discrimination in the United States armed forces.

Davis was the first African-American to rise to the rank of brigadier general. He was the father of the first black officer of the US Air Force, General Benjamin O. Davis Jr. According to historian Russell Weigley, his career is significant not for his personal accomplishments, because he was only allowed a limited range of responsibilities, but as an indicator of a small forward movement for African Americans in the United States Army in the World War II era.

From July 1953 through June 1961, Davis served as a member of the American Battle Monuments Commission.

Davis died on November 26, 1970, at Great Lakes Naval Hospital in Chicago, Illinois, and was buried with his wife Sade Overton at Arlington National Cemetery.

In January 1997 the U.S. Postal Service issued a stamp in their Black Heritage Stamp series to honor the service and contributions of Brigadier General Benjamin O. Davis.

Sylvia Mendez

Sylvia Mendez was born in 1936 in Santa Ana, California. Her parents were Gonzalo Mendez, an immigrant from Mexico who had a successful agricultural business, and Felicitas Mendez, a native of Juncos, Puerto Rico. The family moved to Westminster, CA to tend a farm.

In the 1940s, there were only two schools in Westminster: Hoover Elementary and 17th Street Elementary. The district mandated separate campuses for Hispanics and Whites. In 1944, when she was eight, her family tried to register Sylvia and her brothers at a nearby Westminster elementary school. However, the public school did not admit Hispanic students, and the family was told to enroll the Mendez children at Hoover Elementary School, which was specifically for Mexican Americans. Hoover Elementary was a two-room wooden shack in the middle of the city's Mexican neighborhood. After appeals to Westminster’s principal and the county school board were unsuccessful, Gonzalo Mendez decided to take legal action. On March 2, 1945, he hired civil rights attorney David Marcus, who filed a federal lawsuit with four other Mexican-American fathers from the Gomez, Palomino, Estrada, and Ramirez families in federal court in Los Angeles against four Orange County school districts.

On February 18, 1946, Judge Paul J. McCormick ruled in favor of Mendez and his co-plaintiffs. However, the school district appealed. Several organizations joined the appellate case as amicus curiae, including the ACLU, American Jewish Congress, Japanese American Citizens League, and the NAACP which was represented by Thurgood Marshall. More than a year later, on April 14, 1947, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the district court's ruling in Mendez v. Westminster in favor of the Mexican families. After the ruling was upheld on appeal, then-Governor Earl Warren moved to desegregate all public schools and other public spaces in California. This paved the way for the end of school segregation in the entire country in 1954 in Brown v. Board of Education.

After retiring from a career as a pediatric nurse, Ms. Mendez devoted her life to telling the story of her family and the legacy of the case, and in 2011 she received the Presidential Medal of Freedom from President Obama for her advocacy for educational opportunity for “children of all backgrounds and all walks of life.”

To learn more about the Sylvia Mendez School click here http://sylviamendezschool.org/who-is-sylvia-mendez

Dr. Ionia Rollin Whipper

Dr. Ionia Rollin Whipper was born September 8, 1872 in Beaufort, South Carolina. She was one of three surviving children born to author and diarist Frances Anne Rollin and Judge William James Whipper.

By 1878, as the Reconstruction period was ending in South Carolina, Frances Rollin Whipper moved Winifred, Ionia, and Leigh to Washington, D.C. The family established a home on 6th Street NW, and Whipper saw the children through early education and graduation from Howard University. Ionia, after teaching for ten years in the Washington, D.C. public school system, entered Howard Medical School, one of the few schools in the country to accept women.

In 1903, Ionia graduated from Howard University Medical School with a major in Obstetrics, one of four women in her class. That year, she became a resident physician at Tuskegee Institute, Alabama, and on her return to Washington, D.C, set up private practice at 511 Florida Avenue NW, where she accepted only women patients.

In 1921, Dr. Whipper began a tour through the South as an assistant medical officer for the Children’s Bureau of the U.S. Department of Labor. Her mission was to instruct midwives in childbirth procedures. She described in her diary the less than ideal circumstances she encountered there, including prejudice from whites, and suspicion from blacks.

After her tour Dr. Whipper returned to private practice in Washington where she joined the Maternity Ward staff of Freedman’s Hospital. Moved by the plights of numerous unwed teenagers she assisted there, she began to mentor girls in need. There were no facilities in the area serving black women and girls, and Dr. Whipper began to take individual girls under her wing in her own home and office on Florida Avenue.

Dr. Whipper assisted the girls through their pregnancies and afterwards with infant health care. She soon enlisted seven women friends among her AME St. Luke’s Church members and together they began to raise money for a home that would shelter unwed pregnant girls.

By 1931, the group purchased 3 ½ acres in Northeast Washington, D.C. which became the first Ionia R. Whipper Home for Unwed Mothers. Notably for that time, the home was open to all regardless of race or religion. Dr. Whipper continued to run the home until the early 1950s. Until the 1960s, when similar facilities for whites were desegregated, it was the city's only maternity home that admitted young African-American women. It relocated in 1955 to a different location, and it is still operating today.

Ionia Rollin Whipper spent the last years of her life residing with her family in Saratoga Springs, N.Y. and at the home of her niece, Lelia Frances Whipper in New York City. She died at Harlem Hospital on April 13, 1953, and is interred in the columbarium at Fresh Pond Crematory.

To learn more click the link: http://ioniawhipperhome.org/

Mary White Ovington

Mary White Ovington was born April 11, 1865 in Brooklyn to parents who supported women's rights and the abolition of slavery. As a young woman, Ovington decided to join the civil rights movement after hearing Frederick Douglass speak at a Brooklyn church.

Ovington helped to establish the Greenpoint Settlement in Brooklyn and a few years later Greenwich House Committee on Social Investigations in 1904. There, she spent the next five years studying the employment and housing problems of Manhattan's Black community.

Ovington threw herself fully into the cause of civil rights for Black Americans after reading an article in 1908 that described a race riot that led to seven deaths, the destruction of 40 homes and 24 businesses, and 107 indictments against rioters in Abraham Lincoln's hometown of Springfield, Illinois. The author, William English Walling, ended the article with a rallying cry to come to the aid of the embattled Black community.