Advancing Health Equity

Social Determinants of Health, Health Equity and Its Relationship to Built Environment and Human Behavior

Health starts in our homes, schools, workplaces, neighborhoods, and communities. Health is more than just the absence of disease or infirmity; it is a state of total physical, mental, and social well-being. Every human being, regardless of ethnicity, religion, political belief, economic or social situation, has the right to the best possible health.

What are the Social Determinants of Health?

The Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) are factors that influence a wide range of quality-of-life outcomes in the places where individuals are born, live, learn, work, play, worship and age. The five domains of the SDOH are economic stability, education access and quality, health care access and quality, neighborhood and built environment, and social and community context. Accessible and safe housing, accessible public transportation, and welcoming communities can improve our ability to live a healthy life; whereas intolerance, discrimination, and violence limit opportunities to engage in healthy behaviors.

Over the last two decades, research has revealed the powerful role of social factors outside of traditional medical care in shaping health. While medical care certainly influences health, it is not the only influence on health. Evidence shows that medical care may be more limited than previously thought when determining who becomes sick or injured in the first place.

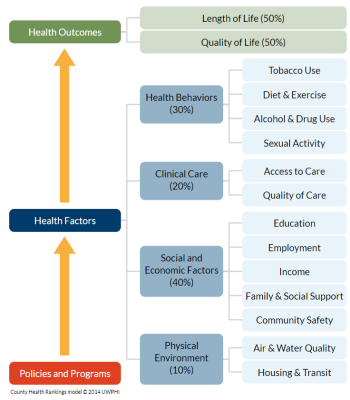

One of the greatest predictors of someone's health or lifespan is their zip code, and it can have a greater impact on your health than your genetic code or healthcare. The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation created an interactive tool to illustrate the difference in life expectancies based on zip code and how it may differ to state or national averages. Features of our neighborhoods such as walkability and access to recreational areas and healthy foods can influence health-related behaviors and provide a more complete picture of these social determinants of health. This interactive model that is pictured was created by the County Health Rankings to illustrate the key factors that can affect health. Furthermore, numerous studies have assessed the impact of social factors on health. A review by McGinnis et al. estimated that medical care was responsible for only 10%–15% of preventable mortality in the U.S. Meanwhile, about half of all deaths in the U.S. involve behavioral factors. Social factors including income, education, and employment can strongly influence health-related behaviors.

The Social Determinants of Health brings to light widespread health inequities and disparities. The WHO defines health equity as “the absence of unfair and avoidable remediable differences in health among population groups defined socially, economically, demographically, or geographically." More simply, the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation states, “Health equity means that everyone has a fair and just opportunity to be as healthy as possible.”

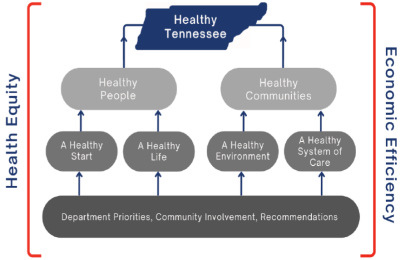

When there is equity in healthcare, there will be equality in health. To achieve health equity, communities must address disparities in access to health-promoting systems and resources such as housing, transportation, jobs, parks and recreation facilities, food, medical care, and neighborhoods, as well as the quality, cost, and safety of those systems and resources. Cities should collect data to learn how groups are affected differently by health challenges; engage residents on the barriers they face in accessing health-promoting services and amenities; and evaluate the potential health impacts of programs, projects, policies, and plans to better understand local health inequities.

What Causes Health Inequities?

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), health and sickness follows a social gradient. The more socioeconomic vulnerability someone has resultsin diminished access to health. The environment where individuals are born, live, and work as well as their access to power, resources, and social capital (the "social determinants of health") all contribute to this downward trend. Examples of these circumstances include education, income, social protection, access to quality health services and good nutrition, access to healthy housing and clean air, and access to financial and judicial services.

Discrimination, stereotyping, and prejudice exacerbate the poor quality of these situations. This occurs not only within individuals, but also within our institutions resulting in underrepresentation of entire populations in all levels of decision-making.

How The Built Environment Relates to SDOH and Health Equity

Cities and communities are the stages where we play our daily lives. These stages, known collectively as the “built environment,” influence how we view and understand the world, ourselves, and each other. According to the CDC, the built environment comprises "all of the physical components of where we live and work,". Our homes, offices, streets, communities, infrastructure, buildings, parks, trails, as well as vacant properties that once housed structures, are all examples of the built environment.

Intolerant policies, histories of segregation, and decades of local disinvestment are all factors that fosters health inequities in the built environment. Lack of access to fresh, healthy food can lead to high rates of obesity and cardiovascular disease. Lack of safe, public gathering spaces can lead to depression, isolation, and other mental health issues. Low-quality stormwater and sewer infrastructure can lead to indoor flooding or closer proximity to toxic water that can cause serious health problems. Poor ventilation in homes that may be located near industrial facilities can lead to high rates of asthma and respiratory diseases in children and adults. Cities must examine discrepancies in the built environment and understand how they came to be when instituting ways to promote positive health outcomes and eliminate health inequities in their communities.

The Built Environment can be Broken Into Six Domains.

The location of a residence has health implications. Proximity to grocery stores, jobs, high-quality parks, and clean transportation alternatives can encourage good health; however, proximity to crime, violence, neglected parks, floodplains, polluting transportation, and factories can result in poor health outcomes. The three key areas built environment interventions need to address when targeting housing challenges are ensuring accessible and high-quality housing that is safe from environmental hazards and close to health-promoting amenities like parks, grocery stores, and public transportation options, ensuring affordability, and remediating unsafe housing to prevent illness and injury.

Providing residents with easy and safe ways to exercise and engage in regular physical activity is an effective strategy to promote health. Residents are more inclined to be active in neighborhoods that are safe, walkable, and have enticing amenities. Meanwhile, residents in communities with poor parks, high crime rates, and dangerous sidewalks may be discouraged from walking, riding, or playing outside. Most built environment interventions for active living focus on making streets safer for pedestrians and cyclists by installing crosswalks, sidewalks, and bike lanes. Trails, pedestrian paths, and parks and recreation centers are among the most popular interventions. These interventions can improve a community’s walkability and encourage individuals to engage in more physical activity for both recreation and transportation. Additionally, these amenities add economic value to a community by creating greater access to already available institutions.

Public infrastructure includes the physical systems, structures, and networks that offer services like water, energy, transportation, and the internet. Effective and efficient infrastructure is critical to our national and local economy, overall quality of life, and communities' short- and long-term environmental quality (clean air, water, and land). Ineffective policies and insufficient government funding leads to infrastructure neglect, deterioration, and decay. Infrastructure degradation has a disproportionately negative impact on poor and minority communities.

The built environment impacts the residents' ability to access nutritious food. Nearby grocery stores and farmers' markets can ensure abundant healthy foods in communities. Whereas poor built environment design includes the reliance on fast food restaurants and corner stores for food. Land use policies determine grocery store location and presence or absence of urban agriculture. Local economic development and planning organizations often decide where new grocery and corner stores can be built, and zone land for various uses, including commercial real estate, agricultural purposes, and urban farming. These planning organizations can also prohibit certain businesses from operating in certain areas, such as liquor stores or smoke shops.

Vacant land and abandoned structures can wreak havoc on public health. Empty properties are a key indicator of neighborhood misery, putting homeowners' and neighbors' health and safety at risk. Blighted properties in a neighborhood produce an environment of social and psychological instability, inviting criminal activity and violence and serving as a breeding ground for rats, mice, and other disease-carrying vectors. People who live near vacant properties are at a higher risk to exposure to crime and other traumas that lead to chronic illness. Demolition of derelict dwellings and abandoned buildings in addition to urban re-greening treatments can reverse these negative effects. The production, preservation, and development of parks, public green spaces, gardens, natural habitats, and greenways are all considered part of urban greening.

Neighborhood design characteristics that increase accessibility, options for active transportation and mobility, perceptions of safety, and attractiveness are associated with physical activity and mental health. These design characteristics include access to community assets, places of employment, businesses, shops, restaurants, entertainment venues, community centers, and other social and commercial infrastructure. Bike routes, parks and open spaces, sidewalks, and good public transit promotes physical activity and active mobility by providing access to the previously mentioned community assets. In addition, attractiveness of the neighborhood, including the level of upkeep and tree-lined streets, perception of safety such as low levels of car traffic, good street lighting, and crime preventive infrastructure is key in the accessibility and use of community assets.

Heights Line in Memphis

The CDC has identified that transportation policy should encourage healthy community design, promote safe and convenient opportunities for physical activity, reduce human exposure to air pollution, and ensure that all people have access to safe, healthy, and affordable transportation. However, active modes of transportation have declined due communities viewing walking or bicycling as unsafe because of unequal road access. Most streets are designed as car centric multi lane through ways that encourage speeding and accidents. Furthermore, the exposure to the harmful air particles and carbon emissions negatively affects the quality of the air and water. This disproportionately affects already vulnerable populations by restricting access to not only a healthy environment but access to jobs, school, health care, and healthy foods.

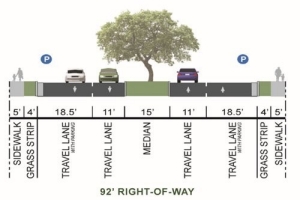

Work to center the lives of communities began by the establishment of Complete Streets Policy and BLDG Memphis (formerly called Community Development Council of Greater Memphis). Complete streets balance the safety and accessibility for all individuals on the road, whether they are walking, biking, using public transit, or driving; and BLDG Memphis established the importance of land use, transportation, and increasing the public participation in planning and development decisions. In response, communities living in downtown Memphis and extending neighboring district have worked to reclaim unused or unsafe road usage

In 2013, Heights CDC was founded out of a community wide need for better housing and a safer community. This groups provides the community with tools of empowerment such as access to affordable housing and the development shared community spaces like libraries, parks, or the streets. Within Heights CDC, the Heights Line initiative is neighborhood led project that is reclaiming road space on National Street. This initiative began in 2017 when the members of the community installed temporary benches and garden beds to reduce the excess road capacity and reduce excessive speeding of cars. In its completion, it will be the longest linear park in Memphis and connect the neighborhood to nearby parks by connecting the Shelby Farms Greenline/Hampline with the Wolf River Greenway. This work will rekindle a stronger community identity and establish a safer environment for any individual that finds National Street central to their life. Through both state and community led initiatives, Memphis has become a standard to look to for cities that are looking to promote greater community prosperity and health through key shifts in the built environment.

Farmers' Market at River’s Park in Centerville

In a 2018 report, Tennessee Advisory Commission on Intergovernmental Relations stated that 21% of Tennesseans live in a region classified as a “food desert”; the lack of affordable access to healthy food occurs at rates higher than national averages. Building regulations, zoning, and lack of investment in communities creates a built environment without access to fresh foods through grocery stores and a reliance on fast foods or processed foods. Food insecurity increases the risk of chronic diseases, obesity, cancer, and premature mortality. Interventions for food insecurity need to reduce the cost of access.

In 2010, Hickman County was identified as a food desert. More than a third of the population had limited access to healthy or fresh foods; moreover, a third of Hickman County residents were considered obese. At the time, Hickman County only had one farmer’s market; as a result, vendors would have to take their produce to more profitable neighboring counties. Hickman county did not have the resources to promote or transform the program; but in 2014, they received a CDC grant to prevent and Control Diabetes, Heart Disease, Obesity and Associated Rick Factors and Promote School Health. Research shows that emphasis on education and community outreach is key for communities to be more likely to take advantage of fresh food opportunities. Furthermore, in 2017, Hickman County received the Healthy Built Environment grant that allowed them to install an outdoor athletic equipment nearby the farmers' market!

The Hickman County Health Department met with the farmers' market program and community members to reinvent and promote the farmer’s market. This not only provided greater opportunities to cheaper fresh food, but more local vendors had the opportunity to join the farmers' markets and sell out of their products. Prior to the program there were only 2 permanent vendors, but there are now almost 20 permanent vendors! In fact, farmers' markets provides three times the return of revenue to the local economy in addition to an expansion to the local job market.

As farmers' markets continue to expand, local farmers and Tennesseans should be aware of The Farmers' Market Nutrition Program (FMNP). This program provides greater access to healthy foods by giving vouchers to eligible seniors and WIC recipients to spend at select farmers markets like the one in Hickman County. More information about the participating Farmer's Markets can be found at www.picktnproducts.org.

Braveman, P., & Gottlieb, L. (2014). The Social Determinants of Health: It’s Time to Consider the Causes of the Causes. Public Health Reports, 129(1_suppl2), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/00333549141291s206

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). (2011). “Impact of the Built Environment on Health.” CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyplaces/factsheets.htm

Erwin D.E., & Schilling J. (2017, April 11). Urban Blight and Public Health: Addressing the Impact of Substandard Housing, Abandoned Buildings, and Vacant Lots. Washington, DC Urban Institute. Retrieved June 15, 2022, from https://www.urban.org/research/publication/urban-blight-and-public-health

Fedorowicz M., Schilling J., Bramhall E., Bieretz B., Su Y., Brown S. (2020, July 14). Leveraging the Built Environment for Health Equity. Urban Institute. Retrieved June 5, 2022, from https://www.urban.org/research/publication/leveraging-built-environment-health-equity

Frank, L. D., Schmid, T. L., Sallis, J. F., Chapman, J., & Saelens, B. E. (2005). Linking objectively measured physical activity with objectively measured urban form: findings from SMARTRAQ. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 28(2 Suppl 2), 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2004.11.001

Healthy People 2030, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. Social Determinants of Health | health.gov. (n.d.). Retrieved June 6th, 2022, from https://health.gov/healthypeople/objectives-and-data/social-determinants-health

Institute of Medicine (US) and National Research Council (US) Committee on Childhood Obesity Prevention Actions for Local Governments, Parker, L., Burns, A. C., & Sanchez, E. (Eds.). (2009). Local Government Actions to Prevent Childhood Obesity. Washington, DC: National Academies Press (US).

McGinnis, J. M., Williams-Russo, P., & Knickman, J. R. (2002). The Case for More Active Policy Attention To Health Promotion. Health Affairs, 21(2), 78–93. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.21.2.78

World Health Organization, (WHO). (2022). Health definition. https://www.who.int/about/governance/constitution

For comments or suggestions concerning this web content, please contact Mariagorathy Okonkwo at mariagorathy.n.okonkwo@tn.gov.