Rabies

Rabies is a viral disease of mammals most often transmitted through the bite of a rabid animal. The vast majority of rabies cases reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) each year occur in wild animals like raccoons, skunks, bats, foxes, and coyotes.

The rabies virus infects the central nervous system (CNS), ultimately causing encephalitis and death.

Need to Report an Animal Bite?

You should report animal bites from wild animals and domestic pets to your local health department, and local animal control office. It's important to call and report animal bites to ensure that you are getting the best, most appropriate information about next steps.

- Description of the animal

- How the bite occurred

- If it is a pet, who owns it and where it lives.

- Get the pet owner’s name, address, and telephone number.

- Find out if the animal has a current rabies vaccination and write down the rabies tag number and year the animal received the vaccination.

- If it is wild, where it currently is and whether it is alive.

Resources:

Find Rabies Treatment

Frequently Asked Questions

Tennessee law does not specify whether 1-year or 3-year rabies vaccines must be used, although local jurisdictions may have stricter laws. “Currently vaccinated” means that an animal’s first vaccine was given at least 28 days previously and booster doses have been given according to the vaccine label. The revaccination date on a vaccine certificate should match the labeled duration of the vaccine used (i.e. if a 3-year vaccine is given, the revaccination date should not be recorded on the certificate as 1 year later, unless it was the animal’s first vaccination).

No vaccine is 100% effective, but rabies in vaccinated animals is extremely rare. One study found that only 2 out of 1,104 rabid dogs were currently vaccinated. If rabies is diagnosed in a currently vaccinated animal, it should be reported to the state health department so that a thorough investigation can be conducted.

Antibody titers are not accepted in lieu of rabies vaccination in Tennessee. Titers are only one marker of immunity and may not indicate complete protection. Other immunologic factors also play a role in preventing rabies, and as yet we have no way to measure those. If a pet owner and his or her veterinarian feel that vaccination is too risky for an animal due to a history of severe vaccine reactions or underlying illness, they may choose not to vaccinate the animal. However, if the pet is exposed to a rabid animal, it must then either be euthanized or strictly isolated for 6 months. If a healthy unvaccinated pet bites a person, there will only be a 10-day observation period required (the same as for vaccinated animals).

If a person is bitten by a wild carnivore (e.g. raccoon, skunk, fox) or a bat, the animal should be killed and tested for rabies, if possible. Be careful not to destroy the animal’s head. Contact your local health department or animal control agency to arrange for testing. Discuss with public health officials at the local or state health department and your physician whether to begin rabies post-exposure prophylaxis immediately or await test results. In many cases rabies testing can be completed within 24 hours.

If your dog or cat has fought with a wild carnivore (e.g. raccoon, skunk, fox) or had direct contact with a bat and is:

• Vaccinated (whether vaccination is current or not): See your veterinarian for a rabies booster as well as treatment of any injuries. The pet should be observed at home for 45 days and examined by a veterinarian if it shows any signs of illness.

• Never vaccinated: If the wild carnivore tests positive for rabies or is unavailable for testing, the pet should be euthanized or strictly isolated for 6 months. Environmental health specialists from the local health department should be contacted for assistance and follow-up.

If your pet has fought with a wild animal other than a carnivore (e.g. groundhog, wild boar), discuss the situation with a public health official from the local or state health department. The species involved and the local rabies epidemiology will be considered in determining a course of action.

If the wild animal has not been in contact with people or pets, review the information from the Tennessee Wildlife Resources Agency about animal damage control and nuisance wildlife: https://www.tn.gov/twra/law-enforcement/wildlife-damage-control.html.

Rabies vaccines are made from killed virus, and very stringent requirements in the manufacturing process ensure that no live virus makes it into a vaccine. There is also a recombinant vaccine for cats in which a protein gene from the rabies virus is incorporated into a different, harmless vector virus. That vaccine is technically a live virus, but it is not the rabies virus. In either case, there is no risk of a person or animal contracting rabies from the vaccine.

There are 2 brands of rabies vaccine for humans. Both are made from killed virus and have excellent efficacy and safety records. The most common side effects of the vaccine, among humans and animals alike, are minor pain and swelling at the injection site.

If a person is bitten by a dog or cat, the animal should be observed for 10 days from the time of the bite. It does not matter whether the animal is vaccinated against rabies or not. If the biting animal is not available for observation, discuss the situation with public health officials from the local or state health department. Rabies is now very rare in dogs and cats due to the effectiveness of vaccination and animal control activities. The chance of any apparently normal, healthy dog or cat transmitting rabies is extremely low, and if a dog or cat remains healthy for 10 days after a bite it could not have transmitted rabies at the time of the bite. If the animal appears ill or abnormal at the time of the bite or during the subsequent 10 days, it should be evaluated by a veterinarian for signs of rabies.

Rabies virus is only present in saliva and nervous tissue (brain and spinal cord) of a rabid animal. It is not present in blood, urine, or other animal products such as skunk spray or bat guano. It may be possible for rabies to be transmitted if saliva or brain tissue of a rabid animal comes in contact with mucous membranes (e.g. eyes, nose, mouth) or an open wound. A scratch from a rabid animal is not considered an exposure to rabies unless the resulting wound becomes contaminated with fresh saliva. There have been a few documented cases of apparent aerosol exposure resulting in rabies in humans; however, these occurred in a laboratory with concentrated virus and in a cave containing millions of bats. The rabies virus is fragile and does not survive outside the host, so there is no risk of being exposed indirectly (e.g. bat in swimming pool, raccoon eating from dog’s food dish).

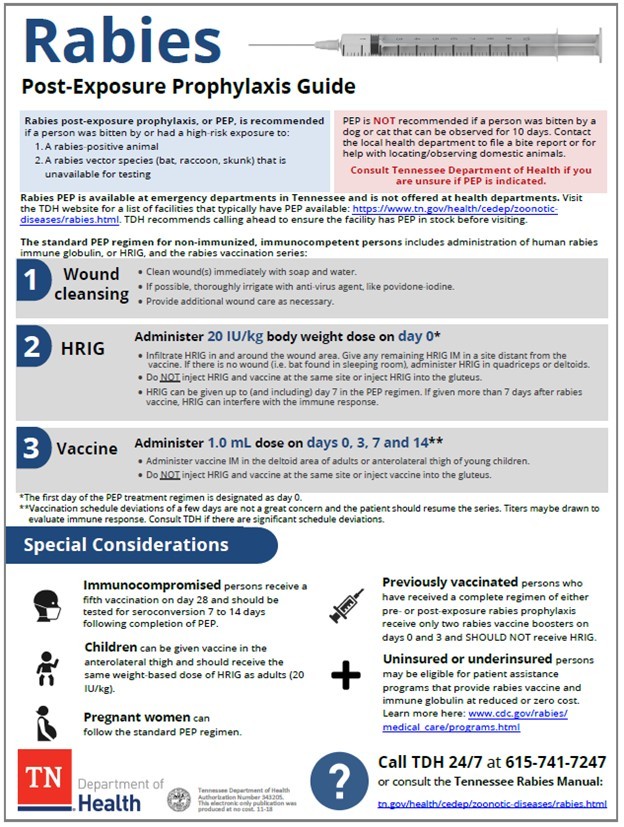

Rabies PEP should be started within a few days after a high-risk exposure (i.e. a bite from a known rabid animal), especially if the bite was to the face, head, or hands. In most animal bite cases, however, there is time to wait for capturing and observing or testing an animal. Rabies PEP is not a medical emergency, and proper wound care should take precedence. Rabies has a long and highly variable incubation period (the time period from initial infection to onset of disease), so PEP may still be effective weeks or even months after a bite.

Health departments in Tennessee do not stock rabies biologics for pre- or post-exposure prophylaxis, but the local health department can provide information on where you can go for care. Generally in Tennessee, only hospital emergency departments stock the products for post-exposure prophylaxis. TDH recommends calling ahead to ensure the facility has rPEP in stock before visiting. After the initiation of PEP, you may be able to return for follow-up doses of vaccine at an outpatient clinic or ask your primary care provider to order vaccine.

If you need pre-exposure vaccination, ask your primary care provider about ordering the vaccine or check with a travel clinic.

Rabies Data

Useful Links

- Rabies Primer (Background information about rabies and rabies control)

- Environmental Health Rabies Tag Finder

- Reportable Disease Page

- Preliminary Data for Animal Rabies (2018-2023)