Why do sounds come first?

By: Dr. Lisa Coons, Chief Academic Officer

When children are first born, we start making faces and cooing sounds. We are constantly talking to our newborns about the weather, naming family members, and identifying everything around them. By talking with our children, we develop language and children hear words and sounds regularly. As newborns become toddlers, we help them identify words and concepts and help them learn more about the world. As children become older, we read to them and share experiences beyond their home, their neighborhood, and their family. We also read seemingly silly books to our children that don’t always make sense like Chicka Chicka Boom Boom and There’s a Wocket in My Pocket! I loved reading these silly books that focused on playing with sounds. At one point, I even had Green Eggs and Ham memorized.

When we read these silly books, why do we say things like “zizzer-zazzer zuzz”, “schloppity-schlopp” or “gluppity glup”? They don’t make any sense and sometimes it is uncomfortable reading words that don’t make sense. Yet, these silly sounds word games were incredibly important for my children and helped them learn to read.

When we play with sounds, we are showing our children how they can play with words and make new words (“real” or “pretend”) by changing the sounds.

As we play with nonsensical words and sounds, we need to emphasize what happens to the words as we are playing with different sounds. We should even encourage our children to play with the sounds within words as well.

Many times, we also use flash cards – a- for apple or a- for ape, and b- for ball, c- for cat, and so on. Using flash cards to match sounds to letters places more importance on the letters than the sounds, and this memorization activity is much different than the sounds word games I described earlier. This memorization does not help children learn to read, and identifying letters as a single sound is not accurate. There are 26 letters in the alphabet, but 44 phonemes (basic sounds) in the English language. Unfortunately, 44 phonemes do not mean 26 sounds plus five extra sounds for long vowels. For example, the sound /th/ is its own sound. So just memorizing letters and the sound match does not actually work when children try to read.

Instead of the letter and sound matching, we need to spend time developing phonemic awareness. Phonemic awareness means focusing on the sounds they hear, playing with the sounds they hear, and manipulating sounds into two words.

We can focus on playing with sounds before learning letters in a variety of ways. For example, we can play with rhyming - “cat, hat, sat.” What other words can rhyme with cat? Also, we can start to count the number of sounds in words. How many sounds do you hear in the word mop? 3, that’s right, /m/, /o/, and /p/ when counting sounds. Start with simple sounds and build to more challenging words. Finally, you can also focus on sounds at the beginning of words such as: how many words start with the sound /p/- pen, pop, park.

We assume that all children pick this up naturally; though, children need practice hearing sounds and manipulating words. Many children can play with sounds through games with family members and teachers.

Our incredible Tennessee teachers across the state are learning how to create more and better opportunities for explicit sounds instruction in their classrooms.

The Tennessee Foundational Skills Curriculum provides crucial building blocks for learning to read by putting a big focus on a sounds-first approach. Students do daily, quick word “games” where they practice “cutting off” sounds within a word and changing sounds. Turning “fall” to “all” or “ball,” for example, helps students hear and isolate the individual sounds within a word, and when our youngest readers then go to read a word in a book, they are better able to break apart the individual sounds in that word.

Watch to see a sample of this:

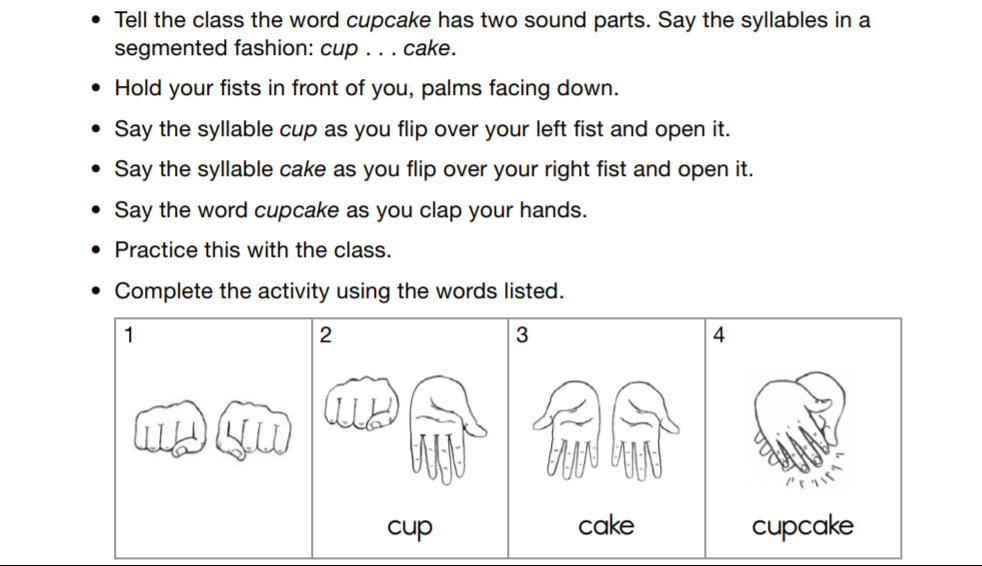

Here is an example of an activity teachers do with students to help practice isolating and bleeding sounds together to become readers:

Want to support your child with some of these activities at home?

Here are some sample games that you can play as a teacher or a family member with your child:

Have fun with sounds and playing with sounds. Hearing sounds first will help your children and your students become successful readers much more quickly than memorizing letters.

References:

Ellefson, M. R., Treiman, R., & Kessler, B. (2009). Learning to label letters by sounds or names: A comparison of England and the United States. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 102(3), 323-341. doi:http://dx.doi.org.proxy.cc.uic.edu/10.1016/j.jecp.2008.05.008

Kilpatrick, D. (2012). Phonological Segmentation Assessment Is Not Enough: A Comparison of Three Phonological Awareness Tests With First and Second Graders. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 27 (2), 150-165. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573512438635Share, D. L. (2004). Knowing letter names and learning letter sounds: A causal connection. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology, 88(3), 213-233. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy.cc.uic.edu/10.1016/j.jecp.2004.03.005

Treiman, R., Sotak, L., & Bowman, M. (2001). The roles of letter names and letter sounds in connecting print and speech. Memory & Cognition, 29(6), 860-873. doi: http://dx.doi.org.proxy.cc.uic.edu/10.3758/BF03196415