Breaking Ground 92 - 55 Years of the DD Act

by Lauren Pearcy, Council Director of Public Policy and Emma Shouse Garton, Council Director of CommunicationsState Councils on Developmental Disabilities, including Tennessee’s, are established by a federal law known as the Developmental Disabilities Assistance and Bill of Rights Act, commonly referred to as “the DD Act”. This law originated from historic legislation signed in 1963 by President John F. Kennedy. The DD Act was unprecedented at the time, because it drew attention to the lives of citizens who had previously been institutionalized, marginalized and even subjected to sterilization and experimentation. Kennedy’s administration ushered in a new era of focus on citizens with developmental disabilities and specifically called for reducing the number of citizens living in institutional settings.

These actions coincided with a broader civil rights movement in America. Alongside the executive actions of the time, community members and grassroots advocacy groups accelerated the progress of the DD Act and other disability laws throughout the 1960s and ‘70s.

Thanks to the unrelenting work by the disability advocacy community, the DD Act has continued to evolve to reflect the most current research and best practices over time. Remarkably, the same founding principles have remained the same: self-determination, independence, productivity, integration and inclusion in all facets of community life for individuals with developmental disabilities. The DD Act’s principles, unparalleled when enacted, are still tested today. State Councils on Developmental Disabilities still look to the DD Act as a guidepost for our work. In everything we do, we look at those principles and ask if our projects and initiatives uphold those values. As the Tennessee Council’s Executive Director, Wanda Willis, often says, “The DD Act is as relevant today as it’s ever been.”

In 1961, President Kennedy convened the first-ever President’s Panel focused on citizens with developmental disabilities. The panel’s findings included the need for more professional expertise about the causes of developmental disabilities, more societal awareness about how to support citizens with developmental disabilities, and enforcement of laws that protect the rights of citizens with developmental disabilities.

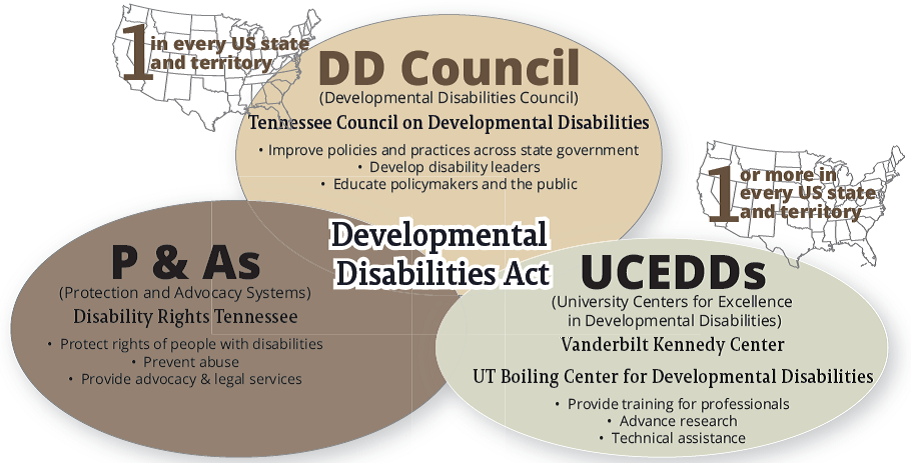

To address those findings, the DD Act created a network of programs that could not only implement change, but help address the cultural barriers facing citizens with disabilities. These three programs together are known as the “DD Network”. Like the Act itself, these programs are still necessary today for addressing persistent gaps in our systems and communities to adequately support people with developmental disabilities and their families that existed 55 years ago.

State Councils on Developmental Disabilities are charged with assessing the overall disability system in their state (or territory) and working to make improvements on behalf of citizens with developmental disabilities. Councils have considerable flexibility to identify their own projects and collaborate with local stakeholders based on their citizens’ unique needs.

Councils are expected to leverage collaboration to make big, lasting impact with relatively small staff and budgets. Most importantly, Councils are expected to empower individuals with disabilities and their families to exert influence over the disability system; that is, the policies and practices that affect their lives. Accordingly, Council members are individuals with disabilities and family members of people with disabilities, which comprise 60% of membership. The remaining members are representatives of State agencies who oversee disability policy and services. Membership necessitates direct interaction between policymakers and the citizens they impact. Representatives of the other DD Network programs also serve on the Council. In Tennessee, the Council on Developmental Disabilities is an independent office in the executive branch of State government.

Protection and Advocacy (P&A) systems exist to protect the legal and human rights of individuals with developmental disabilities through a mix of legal action and proactive advocacy. They work to inform people of their rights, investigate suspected abuse and neglect and provide free legal representation to people with disabilities. They have broad legal authority to access records, facilities, and individuals when conducting investigations, placing them in a unique position to detect and address abuse. Protection and Advocacy systems also serve individuals with behavioral or mental health diagnoses. In Tennessee, the P & A is Disability Rights Tennessee, a nonprofit legal services organization.

University Centers for Excellence in Developmental Disabilities (UCEDDs) were created to address the significant need for professional expertise in developmental disabilities. Today, UCEDDs offer cross-discipline training, technical assistance, and continuing education to professionals and community members. They conduct cutting-edge research, public policy analysis and broad information dissemination efforts. Many UCEDDs offer direct services to different populations of individuals with disabilities and lead model demonstration projects. In Tennessee, we are fortunate to have two UCEDDs: the Boling Center at the University of Tennessee in Memphis and the Kennedy Center at Vanderbilt University in Nashville.

All DD Network programs are expected to be “carried out in a manner consistent with the principles of the DD Act”, which unites the programs as natural partners. In Tennessee, the programs partner extensively, serving on each other’s boards, meeting regularly and working jointly on projects. In fact, the Tennessee DD Network’s level of collaboration is praised as a national model.

A few recent examples of the DD Network’s collaboration in Tennessee:

During the national healthcare debate in 2017 when Congress proposed historic changes to the Medicaid program, the DD Network developed an education strategy to ensure elected officials understood the impact of such changes on citizens with disabilities.

Starting in 2016, the Vanderbilt Kennedy Center established a small working group to discuss an emerging best practice in the disability field called “Supported Decision Making”. Since its inception, other DD Network Partners have taken leadership roles as well. Disability Rights Tennessee hosts the workgroup meetings and held the state’s first “grassroots” forum for stakeholders across Tennessee. The Council on Developmental Disabilities has led the agenda development and meeting notes during each workgroup meeting, plus the sponsorship of national expert Jonathan Martinis to inform the workgroup’s efforts.

Nationally, the three programs work closely to influence policy at the federal level. Unlike many other disability organizations, the three DD Network programs exist in the federal government as part of the U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services. This position allows them to maintain close relationships with the other federal programs that impact citizens with disabilities like Medicaid, Vocational Rehabilitation and Special Education. As part of the same bigger system as those programs, the DD Network can be particularly effective at getting information about disability services and relaying feedback from the citizens who utilize those services at the federal level.

Here is an example of how the DD Network is particularly effective at getting information to citizens:

After the federal Home and Community-Based Settings Rule (HCBS Settings Rule) was announced, the national DD Network associations launched a website with information for citizens with disabilities and advocates: https://hcbsadvocacy.org/. The HCBS Settings Rule is an example of a complex and technical rule that was hard for the average citizen to digest, but directly affected many citizens with disabilities, and getting information out to communities was essential. The DD Network was perfectly positioned to assist; in fact, the network’s oversight agency, the Administration on Community Living, was tasked with reviewing states’ plans for compliance with the new rule. Because of this, the DD Network had more insight than virtually any other entity in the country about the rule.

And, here are two examples of how the DD Network gives feedback directly to national policymakers:

First, the DD Network programs in every state have to report regularly to the federal government about the issues affecting citizens with developmental disabilities. The State Councils do this every five years with its “Comprehensive Review and Assessment”, which surveys both private citizens and state agencies that provide disability services.

Additionally, the DD Network programs each have their own associations which engage in policy advocacy in Washington, DC. The directors of those programs regularly author position papers, statements about policy changes and letters directly to policymakers – including Congress – on behalf of citizens with developmental disabilities across the country.

Without the DD Network in federal government, no entity would be dedicated to the perspective of the citizen using disability services. Thanks to the DD Act, people with developmental disabilities have a space inside the federal government for their voices to be prioritized and heard.

The intro to the DD Act makes it very clear:

"Congress finds that disability is a natural part of the human experience that does not diminish the right of individuals with developmental disabilities to live independently, to exert control and choice over their own lives, and to fully participate in and contribute to their communities through full integration and inclusion in the economic, political, social, cultural, and educational mainstream of United States society."