Historical Markers

A Collective and Inclusive Narrative

By Linda T. Wynn, Assistant Director for State Programs

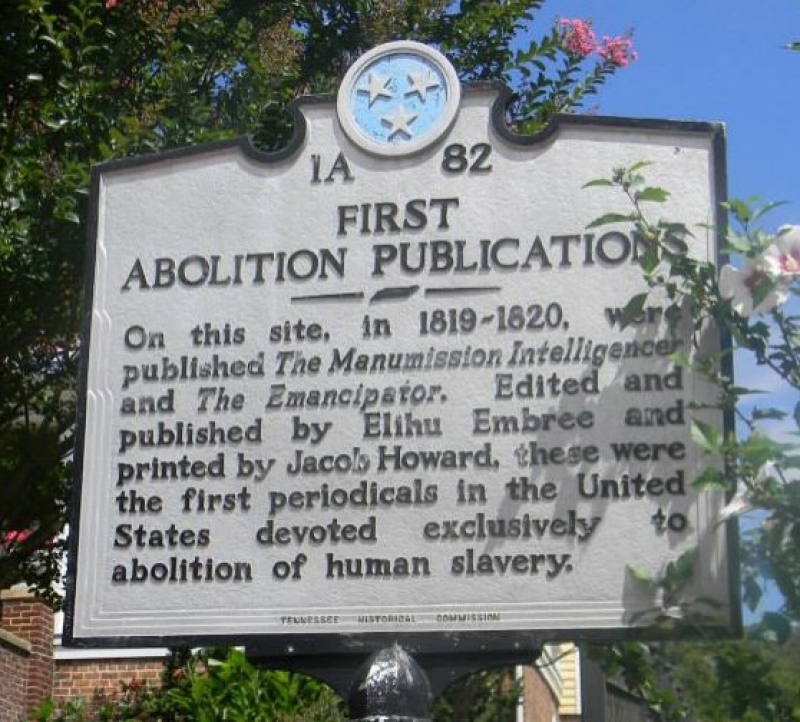

Historical markers are a ubiquitous presence along many state highways and country roads. Tennessee Historical Commission historical markers bear a distinctive three-star logo, with text in black lettering on a silver background. Although these historical markers fall within the sphere of public history, they adhere to the sound methodological approach grounded in the discipline of history. The Tennessee Historical Commission’s Historical Marker Program began in 1948. Since then, the commission has placed more than 2,000 historical markers across the state. Topics range from Abolition to the Civil Rights Movement; from the Civil War to Churches; Enslavement to Education; from Business to Journalism, Music, Animals, and People.

Tennesseans who actively participate in the state’s historical marker program are responsible for the collective and inclusive historical experience that currently dots the highways and byways of the state. A constituent-driven program, persons and/or organizations propose and pay for markers that commemorate events, objects, persons, and places. Like the “traditional history” chronicled by academic historians prior to the 1960s, the state’s marker program initially reflected the experiences and issues most relevant to a small minority—almost all male, white, and affluent. The narratives of African Americans, Native Americans, other people of color, and women were predominantly missing.

Just as scholars began to engage in the process of lifting ordinary people out of historical obscurity, making the ordinary not only consequential, but central to our past and present society and culture, an expanded historical-marking constituency began to broaden awareness of the state’s history and those who contributed to its narrative. Their marker text submissions confronted perceptions that many had come to embrace and intimated that conjecture supporting the notion of a single Tennessee experience was incomplete. Some even required the commission to meet head-on the less commendable aspects of the state’s experience. Their proposals suggested that the historical narrative of the Tennessee experience actually was one of many experiences—each different and each tinted by a different historical frame of reference. Essentially, the historical-marking constituency attempted to bridge the breach between “the ivory tower” and “the real world,” without lessening the significance of either.

The marker titled the “First Abolition Publications,” was erected for a centennial celebration and continues to exemplify one of the state’s 19th Century roadside history lessons. The Manumission Intelligencer and The Emancipator —the first American periodicals devoted exclusively to abolitionist topics— were published in Jonesborough from 1819-1820 by editor Elihu Embree and printer Jacob Howard. Two years later, between 1822 and 1824, Benjamin Lundy, a Quaker, published the Genius of Universal Emancipation, a small monthly paper devoted exclusively to the abolition of enslavement. While in Greeneville, Lundy also published a weekly paper, the Economist and Political Recorder. THC’s marker 1C 53, located on Greenville’s town square, commemorates Lundy’s legacy.

Another centennial celebration that occurred in 2020 and is represented by historical markers is the state’s role in making the 19th Amendment to the United Sates Constitution a reality. The marker dedicated to Anne Dallas Dudley, a Nashville native, tells that she served as president of the Nashville Equal Suffrage League; the Tennessee Equal Suffrage Association; and as vice president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association. In May of 1916, Dudley and others walked from downtown Nashville to Centennial Park to demonstrate their support for the right of women to vote. Markers are dedicated to African American women, such as Juno Frankie Pierce and Dr. Mattie Coleman, who also supported Women’s Suffrage. On May 18, 1920 Pierce spoke at the first meeting of the League of Women Voters of Tennessee, at a meeting in the House Chamber, where she addressed the convention and stated, that African American women supported the right of the franchise for women. The state marker for J. Frankie Pierce does not address her role in the suffrage movement. Another marker denotes Niota native Harry T. Burn, who on August 18, 1920 changed his vote to ratify the Nineteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution. However, a constituent realized that another Tennessean also deserved to be noted for the role that he played in ratifying the 19th Amendment and put forth a text commemorating Yorkville native Banks P. Turner. During the debate on ratification of the 19th Amendment in August 1920, Turner surprised everyone by twice opposing a motion to kill the ratification resolution on the final vote. It was his decisive action which enabled Tennessee to claim its historic role as the 36th and final state to ratify the Amendment that gave 27 million American women the right to vote.

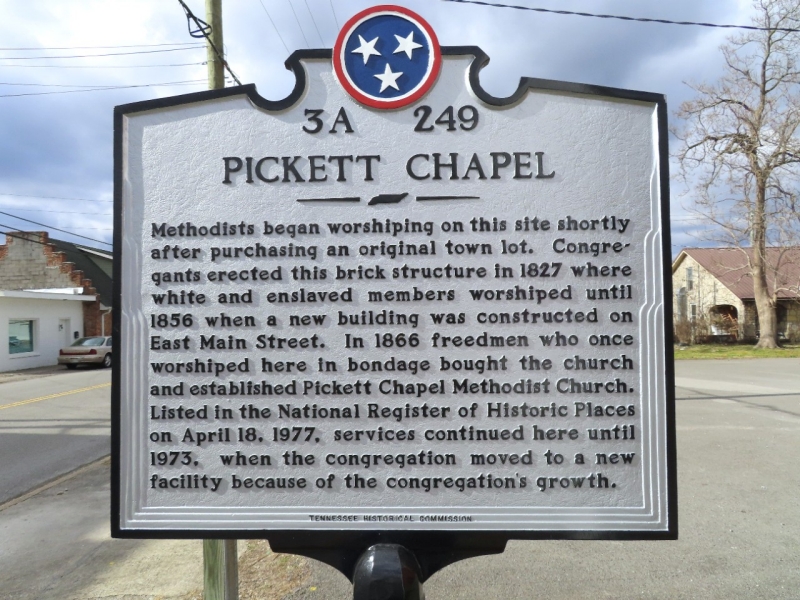

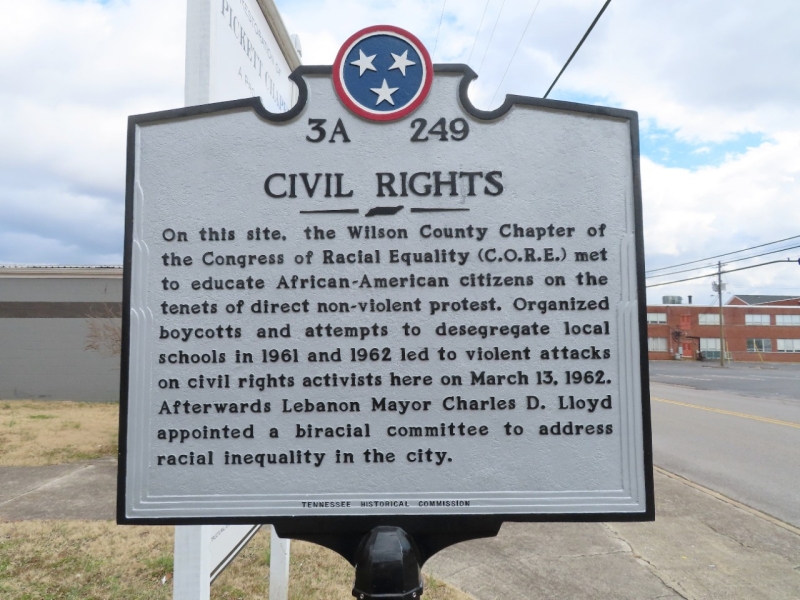

Many submit proposed historical markers, but none are more gratifying than the ones submitted by young people and students who have taken an interest in the history of their local community or school—such as the young man who worked with the Wilson County Black History Committee in obtaining the Pickett Chapel/Civil Rights Movement historical marker. A double-side marker, one side narrates the founding of Pickett Chapel, a Methodist Church in Lebanon, where white and enslaved members worshiped in the same ecclesiastical structure until the end of the Civil War. The other side of the marker informs the public about the Civil Rights Movement in Lebanon when the Wilson County Chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (C.O.R.E.) met to educate African American citizens on the tenets of direct non-violent protest. A true community joint venture, the making of this marker included Sam Bond of Eagle Scout Troop 360, who took on fundraising for the marker as his Eagle Scout Project.

Tennessee Historical Commission markers convey what individuals contribute to their locales, communicate how events that occurred within the state fit into the local, state, and/or national narrative, and elucidate the intersection of race, class, and gender. When put into a collective historical context, one can detect the state’s history through the various topics covered by the markers placed across the eastern, middle, or western regions of the state. They illustrate how all citizens interlace the state’s cultural, economic, political, and social evolution. The stories motorists encounter on state historic markers must be seen not only as contingencies, but also as the legacies of Tennesseans with a common story and mutual fate.

Thirty THC Historical Markers Approved in 2020

February 21st approvals: John McAdams School/Bedford County Training School, Bedford County; Braxton Lee Homestead, Cheatham County; Danny Thomas, Shelby County; Bernard School, Warren County; Rich-In-Tone Records, Washington County; Pickett Chapel/Civil Rights, Wilson County.

July 10th approvals: Pat Head Summitt, Cheatham County; Morris Memorial Building, Inc. Nashville Alumnae Chapter (Pi Chapter), Delta Sigma Theta Sorority, Inc.; Davidson County; Willow Grove Missionary Baptist Church, Dr. Louis Edmundson, and Bethel United Methodist Church, Giles County; Trail of Tears: Cherokee Removal, Hardeman County; Speedway Circle, Mary Frances Housley and First Evangelical Lutheran Church, USA, Knox County; McReynolds High School, Marion County; Caney Fork Baptist Church, Putnam County; The Rose Terrace House, Roane County; Benevolent Cemetery, Rutherford County; St. John Baptist Church, Shelby County; Benjamin Hooker/John Rice and Skirmishes at Rural Hill, Wilson County.

October 16th approvals: “She Jumped the Tracks” Last Words of Fireman J. W. Tummins and Jellico’s First Commercial Airport, Campbell County; Davis Creek Primitive Baptist Church, Claiborne County; Hermitage Springs. Clay County; Centennial of PI Chapter, Alpha Kappa Alpha Sorority, Inc., Davidson County; Sikta School. Gibson County; The Rev. Edmund Kelly and Columbia State Community College: Tennessee’s First Community College, Maury County.